B. Thom Stevenson

Who are you?

I’m B. Thom Stevenson and I’m a multidisciplinary artist.

What do you make?

Painting. Sculpture. I do some performance stuff. I try to make abstractly functional objects, things that are functional in some way but are more based on aesthetics. I like the idea of a painting being a functional object, not just metaphysics. You can see a painting one day and it may mean one thing, but the next it conveys a different message. I want my works to act as a catalyst to this type of introspection as well as fulfilling the physical function of aesthetics. I use a lot of found text in Japanese, Chinese, and German. If you don’t speak the language you guess what it means and if you do speak the language you’ll have a different cultural approach. They’re different angles for people to approach each painting. Like a projective test or a Rorschach Test using more concrete symbols. I also make sculpture with varying degrees of functionality. Like my donation box sculptures, which are receptacles for giving. I lend these out to different charity events to receive donations. They all have dual functions. One’s a planter, one acts as an honor system for reciprocating prints in exchange for donations, and another one is an aquarium.

Do you have a preferred medium?

I like stainless steel a lot. That’s probably one of my favorite materials to use, but it’s also expensive and time-consuming and frustrating because I don’t know how to work with it myself; I use fabricators for that. Three years ago I made seven paintings on stainless steel with enamel and I buried them behind a gallery over here, SIGNAL, in their backyard. They’ve been in the ground there for three years. They dug one up on accident; when they were digging a fire pit they forgot that the paintings were back there. I dug one up too. I like the idea of time as a medium.

Describe your workspace.

Two walls for painting and two walls of windows. I think natural light is important even though I do most of my work at night. There are walls of books and my flat file is pretty full. A bulging flat file. It has everything I need. I think having source material is really important and I try and surround myself with that, even if it’s just a lump of clay. I feel much better when I have a blank canvas around that I can paint on. I have my photocopier, which is a huge part of my process. I collage drawings together with photographs of paintings that I’ve made and some found text and then I use the photocopier to further flatten the image.

Under what conditions do you work best?

If I have a full day that’s definitely the most ideal. It’s rare because I have a day job and I do freelance. I work in spurts and I like to be able to do some drawing for a little bit and then work on a clay sculpture for a bit. Then eventually at the end of the day I’ll come around to a full thing, like I’ll finish a painting. But I think the best condition is definitely if have a full day in the studio. No distractions.

Do you have any rituals surrounding your practice?

I’m weary of being one of those artists that does the same thing forever so I try not to get too process-based—but at the same time I probably do. I think my work is very ritualistic with the image and how I process the image. The way I make a painting is like drawing a sigil; you kind of write out this idea and then you redraw it, redraw it, redraw it, take out letters, take out different parts, put them together, and eventually you create this symbol. So what I try to do is put out all of the elements that I’d like to be in a painting and redraw them, xerox them, draw them again, paint them, sometimes make them into a rug and photograph the rug and make that into a painting. I think my process is more of a reprocessing of images. I guess I’ve developed this ritual with it; I’m kind of becoming idol-esque in a weird way. It reminds me of the Venus of Willendorf or something like that. It was this shape of a woman that became this pure sexual form. It became the bare essentials to reproduction and fertility. I like the idea of re-addressing an image to bring out its pure form. I guess that’d be the ritual. I wouldn’t say it’s a conscious ritual, maybe it’s more like an OCD-type thing.

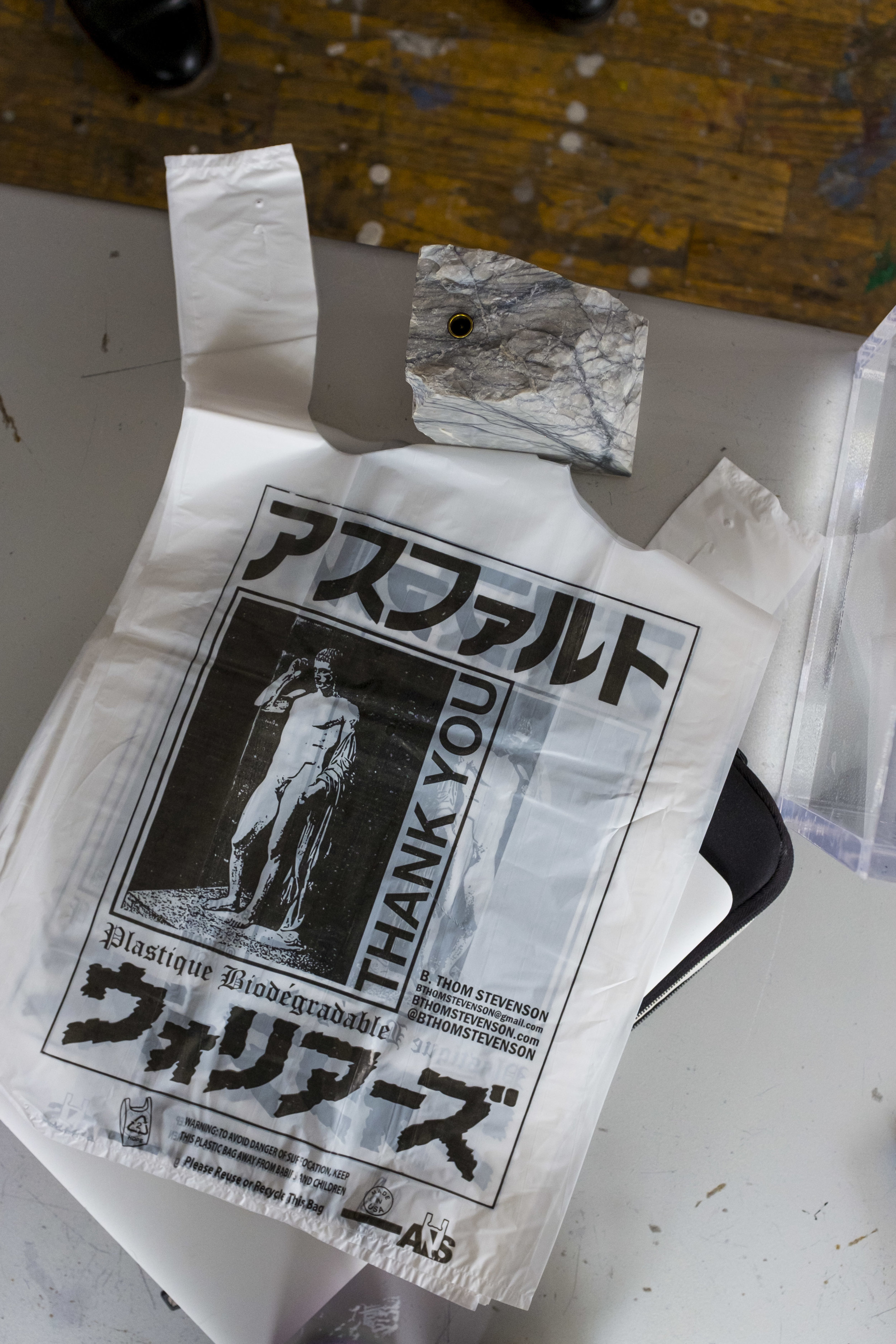

I also like the idea of mass production; that is such a ritualistic thing. They set up these machines to do the same thing over and over and over again. I totally understand Andy Warhol’s fascination with the Campbell’s soup can. Once I made these plastic bags and the minimum to make them was like 5,000 plastic bags. I designed them with a depiction of the Roman statue of Marcellus as Hermes, the Greek god of trade, and they said thank you and they had all of my contact information. I went around to bodegas and gave them the bags. I always liked the idea of commerce working for me because I feel like we always work for commerce. I love the idea of making something that is usable or serves a function that someone can cherish because it’s an art object but also because they can form their own memories with it because it serves a physical function. And I put this image of a marble sculpture on the bags because plastic can last just as long as a marble sculpture, even though they’re those “biodegradable” plastic bags that supposedly will biodegrade under the right environment, like if they’re buried with a certain bacteria. It might be bullshit but I paid extra for it. But that’s why I put them out at bodegas—I’m not trying to add waste to the world, I’m trying to replace the waste. Why not just make disposable goods look good? If we’re going to be filling the landfills, why don’t we fill them with things that people are going to be excited to find in one hundred years?

Describe your process.

I don’t think as many people as you would think paint without knowing what they’re going to be painting. Very seldom do I go out and do that. When I go up to a painting and I have no idea what I’m going to paint, I use a little tabletop easel, but when I know exactly what I’m going to paint I tend to do it on the wall. I think it’s a structure thing, like subconsciously the wall is stronger while the easel is more flexible. With the easel I can grab it and almost sculpt with it because I grab the easel with one hand and paint with the other. But I would say that I very seldom go into a painting not knowing what I’m going to paint. I wear different hats, I’d say. I think it varies between what I’m going to do and the mood that I’m in. With some of my paintings, like the peacekeeping painting, I knew exactly what I wanted to paint. But if the paint drips and stuff like that, I don’t freak out or cover it up. I just let it happen. I let the paint do its thing.

What meanings do artifacts hold for you?

I like the idea of objects as symbols. I like the idea that an artifact, an object traveling through time, has had so many different interactions and impressions on different people and cultures. One symbol can go from culture to culture and influence it, just like the cross. I don’t use the cross that often but I like the idea of the cross and its many different renditions and the many ways it has affected people. I like that twenty people can look at one artifact and each assume something different about it. Especially when it’s a spiritually functional object. I’m not a super spiritual person but I like the idea of something that’s spiritually charged. When you walk into the studio I have a few charms nailed to the pole, and I like sage and things like that. I like the idea of these objects having this mystical feel to them. And repainting them is like an archaeological process. I have all of these old archaeology books from the MET back in the day. Before there were photographs or even during photography when bringing a camera along wasn’t the most stable process, archeologists would do a lot of drawings. By doing that it makes you meditate on the object. I like the idea of meditating on something just by giving it attention through simulacrum.

What roles do language and typography play in your work?

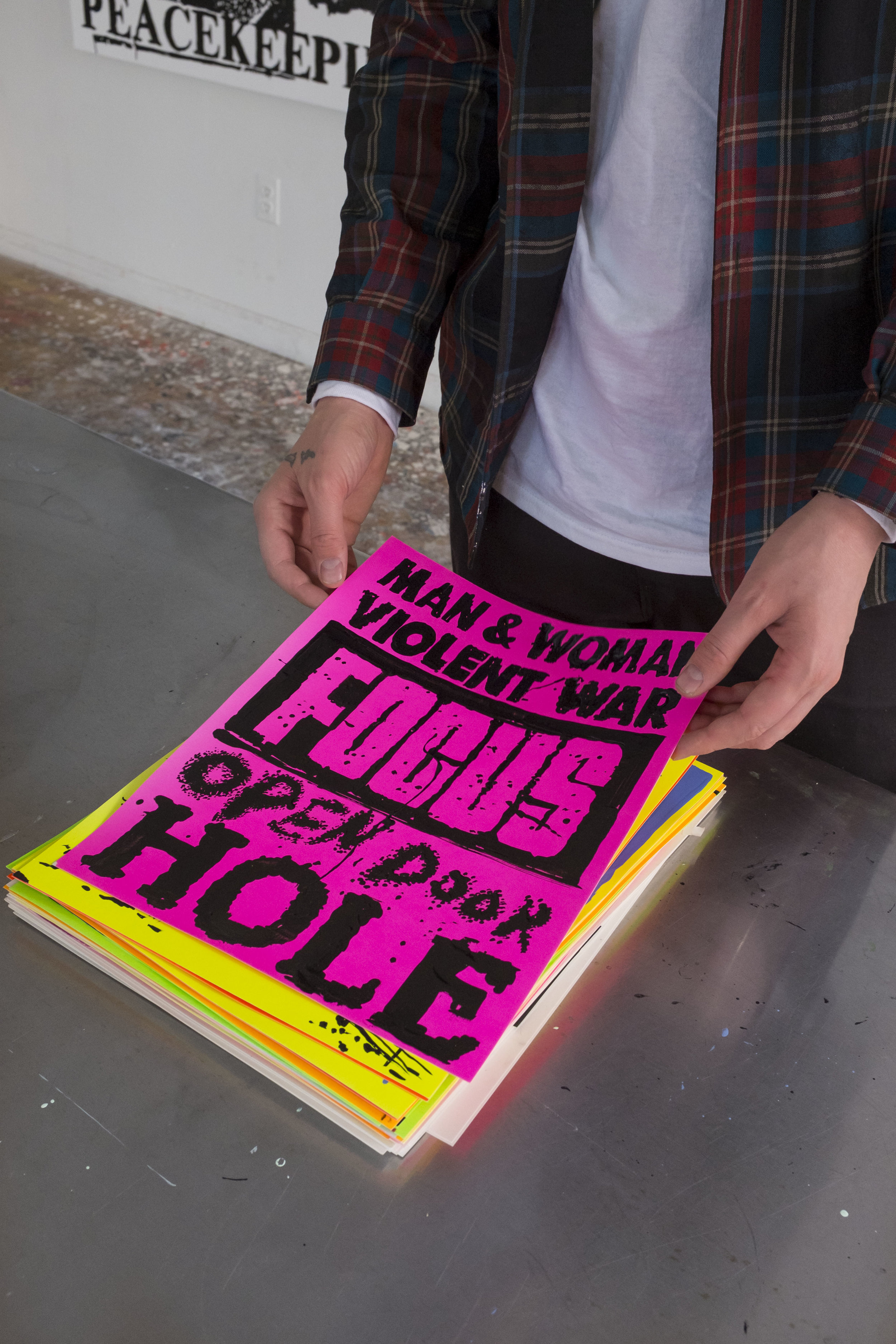

I use books a lot for the text in my work. I don’t like to pull things off of the internet; I feel like it’s cheap. I like to pull pre-existing words. I like the idea that someone else has typeset it, whether they did it real quick and weren’t thinking about it or whether they labored over it. I’m trained in typography and I may have different instincts, so I like the idea of someone else’s hand being in the work. I like the implications of painting words with images. My painting practice is often a heavy handed Dadaist exercise with heavy leaning towards aesthetics rather than chance. I stack text based off the forms of the words in the composition, not what they mean.

What is the most challenging part of your process? Where do you find the most ease?

I’d say the most challenging part is finding time. And then when I have time, that’s probably the easiest part, it’s just painting. I paint for me, I paint because I enjoy it.

Does working in New York have an influence on your practice?

It does. It’s such a convenient city, you know? Like the bodega around the corner is open 24 hours. But at the same time that’s such a distraction. New York has given me so many opportunities. Even material. When I ride the subway home at night, there are those Christian people that give out packets—I always take them. I’ve gotten a few nice lines of text from those too, there’s so much material. Also exposure to other people. It’s not like I go out every night, but I have the option to. I feel like you have some sort of like existential ease in knowing you have these options. That’s the same reason that I surround myself with materials.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

It has made my fingernails dirty, especially working on the clay stuff.

B. Thom Stevenson in Brooklyn, New York on February 10, 2018. Photographs by Julia Girardoni.