Camille Hoffman

Who are you?

My name is Camille Hoffman. I am an artist and a teacher based in New York City, currently in Queens to be specific. In the most general sense those are the labels that I can give myself. I’ve been teaching and working in various communities around the country for the past ten years. Going back and forth between that and painting has always been a very important component of my work; I see that as an extension of my studio practice. So I’m a studio community practitioner.

What do you make?

I make all kinds of things, but currently I am focusing on a series of paintings that uses found materials and mixes them with oil and acrylic. A lot of the materials come from my everyday life, including all sorts of plastics, plastic bags, holiday themed tablecloths, food packaging and nature calendars. I’m using all of these materials to create these fantastical landscapes that reference a history of landscape painting; it’s a very Euro-centric history that I recognize I inherit to some degree as an American artist who has been academically trained here. But at the same time, the paintings expand upon those ideas of the landscape and grapple with how to reshape that terrain into something that includes a very personal narrative and also an imaginary narrative.

Do you have a preferred medium?

Well I’m a painter, first and foremost. That’s always been my thing. So even though I’m working in mixed media and using all of these found materials, I’m still thinking about them like paint. All of my collage materials are divided and organized. Even though I categorize each image by color, they all have their own unique element that they bring to the work. So that being said, I think painting is probably my main medium but I try to think more expansively in terms of what painting can be for me in my practice.

Describe your workspace.

Now that I have the luxury of spreading out in this new studio, I’m trying to organize a little bit better and create different sections for the different processes that I deal with. I have areas with my plastic, I have areas with my collage, and then there is this area to dry out my wet paper-mache. This is really the plushest studio situation that I’ve ever been in. Here I can actually divide these things up and not have to clean an area in order to work on something else.

You’re seeing a very clean version of this space. If you come back in a couple of days there’s going to be shit everywhere, I can promise you that. I have so much shit and it’s hard to always find everything I need, so it helps me to have messy piles so that I can see what I have. Sometimes I forget that I have something if it’s not out. But I’m actually really organized and I like to know where things are, so even when it’s a big mess there’s a logic to it. For example the way that I organize my collage cut-outs is by color.

Describe your process.

I usually start with little sketches. I might have a general compositional idea or a color theme in mind. I start with acrylic and map out general color fields. At that point I also think about what specific collage materials I want to work with. Then I’ll use a lot of painter’s tape to tape on collage elements and see if they work. Sometimes some random shit will fall on the floor and I’ll think, That’s it! This needs to go there! Eventually there ends up being a reason for it too. Once I get to the point where a lot of the collage or paper materials are assembled, I coat the surface with a matte medium to make sure that they’re really protected. Otherwise the oil paint would eat away at the paper. Then I use oil to blend the materials together. The blending is a very important part for me to create a seamlessness between disparate objects.

Sometimes I see my work as a spill; it spills over the side of the frame. Life is fucking messy, you know? There are no clean edges. Sometimes I intend to create that, but it’s just the nature of the material - often paint drips and plastic needs to stretch around a corner. It’s different with different pieces. There is no way that I can plan out pieces entirely because the materials add their own dimension to the work. It’s layered. Often there is a problem that I know needs to be resolved; I have the answer but it takes time to figure it out. I’ve had a couple of days where I just come in and look - I don’t even work, I just stare at a piece. Then other times I just know what to do. Usually that’s after a good night’s sleep. All that is to say that I start out with a general compositional plan but allow for spontaneity and exploration as I go.

Do you have any rituals surrounding your practice?

I do. I’m a meditator. Even just to go about my day, I never feel entirely myself unless I take the time to focus. Usually it’s the first thing I do in the morning - meditate or write. Maybe there is something that I need to plan or prepare for in a day, whether it is teaching or coming to the studio. Sometimes I’m thinking about larger issues like the state of our world and how I am going to navigate that. And sometimes there is something I want to cultivate within myself to counteract the madness that I see increasing around me. Quiet contemplation is a very important part of my daily ritual surrounding my practice and my life.

I do some yoga here and there. And walking. Mindful walking is important to me - or even mindful subway riding. I never know what I am going to learn or who I’ll encounter, but I like to be open. I am always having such interesting exchanges with strangers, there is so much to be said for just smiling at someone. When I am able to spend a lot of time by myself, I end up making the most friends and I find that I am able to be more cognizant of all of the really beautiful things that surround me sensorially. That in turn becomes an important part of my ritual and informs the work that happens in the studio. Facebook and Instagram are also parts of my ritual. I think that there’s a lot of value in the community that social media creates; the fact that I can share updates on my work with my family in the Philippines or my random high school friends is so cool.

What conceptual role do found materials play in your paintings?

Maybe it would make more sense to speak about some of the specific objects. For example one of the main materials that I have been working with for the past three years has been plastic holiday-themed tablecloths. That came about as I was shopping at the dollar store to get regular things for the house. I was really drawn to these tablecloths because they reminded me of a lot of the things that I had growing up when we would celebrate birthdays or Christmas and Hanukkah (I was one of those lucky kids who got to celebrate both). I associated the tablecloths with celebrating and coming together, but at the same time they were disposable objects. On the same day that I came across the tablecloths in the dollar store, I had been doing research on indigenous Filipino textiles at the Yale Art Gallery. They have one of the largest collections of Southeast Asian textiles in the country. As a student, it was a really inspiring and motivating to have that resource available to me because I had never really had access to objects that directly related to my ancestry. So I began to think a lot about what role textiles play in my family’s culture and in a lot of cultures, not only ritualistically speaking but also economically speaking. They’re used as objects that can be bartered and they’re objects that can be passed down through generations, whether it be for wedding ceremonies or funerary purposes. Eventually, I realized that these plastic tablecloths were a contemporary version of what traditional textiles were for my ancestors in the past. Even the patterns in these pseudo-tablecloths are based loosely on some sort of weave. It’s important that the traditions of these tablecloths are maintained and that they still continue to fundamentally bring people together. So then it became my big project to restore and return these very kitschy, disposable objects to some place of sacredness and real personal history. That’s when I really started to cut them, and then I eventually began experimenting with weaving them. From the weaving I started to think about painting with them and not just on them. Then I started to tear them and work them into my paintings to create these vast landscapes. That was the evolution.

As I was starting to work with the tablecloths, I was also collaborating with a friend of mine, Edgar Garcia. He’s a poet, and as an experiment we had a back and forth where he was in my studio writing poetry in response to some of the work that I was making. I started making work in response to his writing and then it all kind of culminated into a narrative about this post-apocalyptic tribe of humans who were attempting to revive forgotten rituals. It got very elaborate and tied in a lot of our autobiographical information. A big part of the narrative was that humans in the future, who were surrounded by plastic and stuff, made a momentous weaving so that they could connect with their ancestors who lived in the stars. I thought to myself, I have to make it and it has to be momentous. So I wove it.

It started off being thirty feet long and then it just grew. I displayed it first for my Yale critique and the setting was a sort of sterile, white box space. Later we took it to an abandoned bible theme park in Waterbury, Connecticut called Holy Land USA. It was wild seeing how the piece operated in different contexts while still thinking about it as a painting. It’s this snakelike painting that I bring into different spaces and each time it becomes something new. After that I actually brought it to Israel with me - I took it to the real holy land in my suitcase and I photographed it in Jerusalem. There is a theme park in Latrun outside of Tel Aviv called Mini Israel, and my friend helped me sneak in and photograph it guerilla style. And then I was also invited to display it at the Yale Art Gallery in the exhibit next to the pieces that I was inspired by to begin with. In the gallery there’s a corridor between the Contemporary Wing and the Indo-Pacific Wing. I think a lot about how works from different parts of the world are framed within the context of a museum; non-western art is usually framed as something that has existed in the past and is not alive and well. So I hung my weaving in the corridor between those two wings. Each time I displayed it I wove more into it. In Israel I bought tablecloths and started weaving them in. For the Yale show I extended it another twelve feet so that it could reach an Ifugao Philippine figure, which is a wooden carved figure, in the Indo-Pacific Wing. It was important to me that it would get that far. So this work is just one example of how my thinking and ideas have revolved around one specific material, but it’s an ongoing process.

What are some of the recurring motifs in your work?

I was talking a little bit before about the landscape tradition that I work with. Being an American artist but also someone who’s based on the east coast, I’ve been thinking a lot about the Hudson River School and a lot about the paintings that emerge from that manifest destiny period. I have a painting called Sunset for Fred Church that kind of riffs off an Ansel Adams photograph. It’s this image about a fascination with the sublime in the American landscape that was happening during the vast industrialization of our country. At the same time, the Chinese were being enslaved to build railroads to get out west and American Indians were being displaced. In these works that are just so visually captivating and so beautiful to look at, there’s something else really embedded in them. I’m interested as an artist in sort of breaking those layers down and creating a space where multiple narratives can be thought about at once. As an American artist and a formally trained painter, I’m questioning what it means to be a multicultural or biracial American, a Filipino-Jewish-American painter, and a woman who’s reinterpreting these paintings that are made by these old white guys. In many ways I feel like I’m having a conversation, and in other ways I like to poke holes. All of these things are circulating around my brain when I develop my landscapes.

Eyeballs are a very important part of my work too. I don’t know if you’ve noticed but in some of my paintings they pop through a lot. They started emerging from the cartoony figures that I was working with. What I’ve realized is that sometimes the meaning comes through the process. When I was researching Southeast Asian textiles I noticed this kind of recurring diamond motif. I was asking the curator, “What does this mean?”, “What do they represent?”. She told me that they’re kind of reflective of eyes. Obviously they’re very abstracted, but it’s sort of the way that ancestors are able to keep their eyes present in the material. When you think about these things being passed down from generation to generation, you realize they’re still with you.

Also gingham. It’s very American, and I’m very curious about why that is and where that comes from. I heard that the word picnic comes from a tradition of lynching in the south. It was supposedly abbreviated from “pick a …” I think it’s actually true, but if nothing else it has made me think a lot about it when I work with this pattern. I’ve heard this from several people and it’s just another layer to this tradition that we think is so classic America. But why is that, you know? How does that carry through in the material? Similarly there is this tablecloth that’s Cinco De Mayo themed. It’s trying to be a textile. But what even is Cinco De Mayo anyway? It’s not even the Mexican Day of Independence; it’s a way for Americans to celebrate or feel some connectedness or just drink. How can this be a fun, kitschy thing and also be an object of violence for that reason? It sort of glazes over an entire culture and history at the cost of our enjoyment and entertainment.

What role does exhibition context play in your work?

I think that’s a challenge for a lot of multimedia or installation artists - negotiating how a piece itself functions and exists and determining how to talk about it outside of exhibition context. That’s a question that I haven’t quite answered for myself. With the woven piece, it was displayed on its own in the gallery. I was invited to come and speak about it, but I obviously can’t always - I don’t always - want to be present to explain the work. I believe that everybody should have their own personal encounter with the work and bring their own feelings and thoughts to it. As my work has evolved it has come to incorporate more photography, which actually came about from documenting my installation with the weaving. So I sort of found this happy medium.

There’s a painting that I did for my thesis where I actually incorporated a photograph of me working; it was when I was first envisioning all the worlds and realms that existed in the fictional narrative that Edgar and I created. I’m at the bottom of the painting with the weaving, and above me is the display case with the Ifugao figure. It’s in the context of the story about the ancestors that reside in the stars, so I made the figure a kind of spaceship that exists in this other realm. So in this case the documentation became a part of the painting. Everything always sort of just folds itself back into place. The more I work I realize that that’s also just the way I live and the way that I interact with other people. It probably drives my friends that are non-artists nuts because I’m always just noticing things. Maybe it’s part of my ADD too, but it’s still all part of the work. My life is a part of my work, and more and more as I work I hope to reflect my life back through what I create. I really see it as a holistic experience. I think it’s a matter of just trusting that process, just working and being honest and being true to yourself. The closer you get to that, the more of the meat and the meaning of the work can come through.

How do community and collaboration play into your work?

Specifically with teaching, I really appreciate that it forces me to reconnect with and reiterate ideas that are fundamental to me now, but that I did have to learn at some point. There is something very grounding about articulating things that I intuitively do every day but that are still fresh to eyes and ears that are just learning. It helps me stay connected to what I make and why I make. That dialogue is just as important as my alone time to meditate and take my walks and paint.

I am always learning from my students. Teaching allows me to not stay in this stagnant place or to be too proud of myself. It keeps me humble and that humility forces me to keep pushing myself and keep trying new things. I also like to steal a lot of ideas from my kindergarteners; they are like a treasure trove. The younger they are the less constrained they are. It’s innocence but there’s also something wise about it. They are more alive than anyone else.

How have you learned what you know? Did you have any teachers or mentors who helped shape you as an artist?

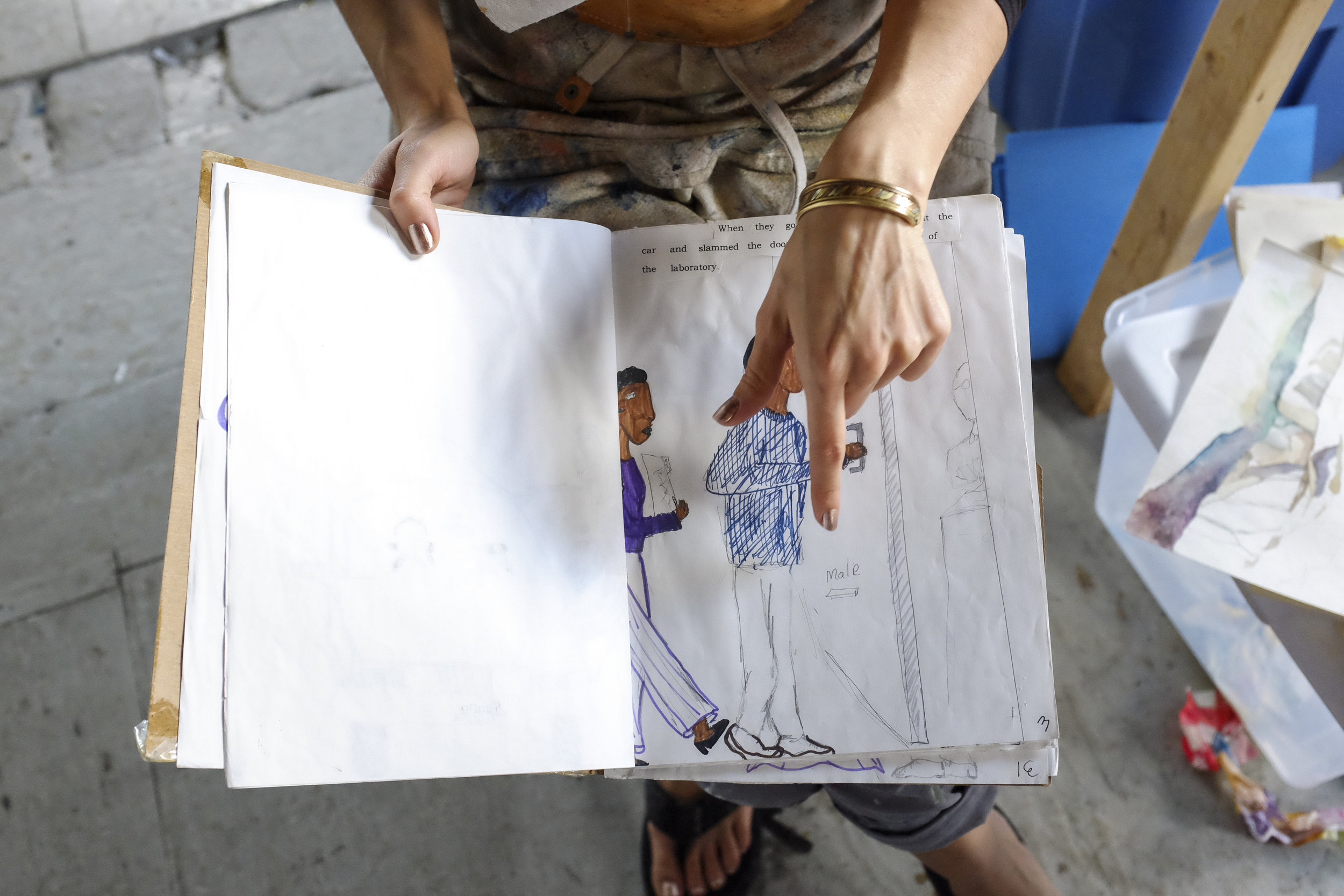

So many. I recently went home and was so happy to find this book that I wrote in fourth grade. It’s called The Mysterious Space Adventure and it’s just so me. I was the same in fourth grade as I am now. Even then I was thinking about other dimensions. This is the most precious thing in my studio right now. I am very very blessed that I had teachers who were encouraging me to do this stuff, to write and to imagine these new worlds.

I was one of those kids that went to a lot of schools. I went to one public magnet school in Chicago, a Spanish immersion school, that was founded by civil rights activists and artists. It was majority Latino and a lot of my friends were immigrants or their parents were immigrants. Built into the content of our day to day lessons were discussions of issues of social justice and multiculturalism. We discussed art as something that could be used as a form of civic engagement. I thought it was normal that in sixth grade we researched the overthrow of the Pinochet regime and the overthrow of Allende and that I wrote a musical about it. And then my family moved to Arizona, and Arizona is a conservative place. I went to a diverse high school, one of the most diverse high schools in Arizona, but I still had to go to these government classes and hear a teacher tell me about how gay marriage was disgusting. That is when it started to hit me how special my experience in Chicago had been. It’s funny that a lot of my friends and colleagues from that experience have ended up becoming artists, activists, teachers, or they’re involved in higher education. It was a very formative time. I still talk to my third grade teacher every three weeks, sometimes more. We have great conversations. He has been very involved in the civil rights movement. In his class we would celebrate Paul Robeson’s birthday and we’d have entire lessons on people like Rosa Parks; it was great. He was a very important teacher to me.

Is there anyone or anything that inspires you?

So much. This is a good question, but it’s so hard to answer because I am constantly drawing references from so many places. I will say my grandmother. She was a Jewish painter and an amazing artist. She was one of the few women to go to the Art Institute in the 1940s. She made some incredible work, but I think that as a result of being Jewish, being a woman and being a difficult person to get along with, she didn’t get nearly the recognition that she deserved. She died when I was ten, but I was very close to her. In my very early years I was always at her house making stuff and then when she died we got all of her work. Now the Illinois State Museum put a nice show together of her work, but back then I grew up with all of her work around. I have a lot of her small paintings in my apartment that I look at a lot, and I still feel her. I think that now even as I develop and as I’m becoming a more mature artist and woman, there are certain things that I see in her paintings that I didn’t see before. Her spirit is still very present.

My dad was also a sort of self-taught art historian and dealer, so my relationship with my father was him lecturing me about art all the time. He’d take me to antique shops and junk shops, so I learned a lot and I took a lot in. His focus, also the era of my grandmother, was mid-century American art - the social realists and the WPA period, very political work.

Then there’s my great uncle who was my grandmother’s older brother, Mitchell Siporin. He was an important WPA muralist, especially in Chicago. He did these major murals, there was one at a public high school. That is a legacy that I am very proud of and proud to be a part of. There is also this whole bookshelf of inspiration, but that is just the beginning.

What is the most challenging part of your process?

I am really blessed right now to be in this space and to be awarded this residency. Opportunities like this haven’t come up for me a lot in the past. I think that just financially funding my career and having the luxury of space and time to create amidst the need to pay bills and feed myself has been my biggest challenge. I was supporting my family even when I was in high school, so I can’t ask them to begin to support me. My mom is an artist too, so at least I have that moral support.

I think that there are other parts of the process that don’t come naturally to me and I’m still learning to navigate them. I am a very community oriented person, but there is an aspect to the art world that involves a lot of politics. I don’t really like to integrate myself into that. I am finding my own path. I find that the more I do what I love to do, interact in the way that I like to interact, and surround myself with people who feel the same way and live by the principles of kindness and community, the more I find my tribe and success on my own terms.

What has your practice taught you?

It has taught me a lot about process. Things take time, ideas need to develop. It has taught me a lot about trusting my instincts and approaching challenges with more critical, abstract, complex, nuanced thinking. It has taught me to see the world from a more multilayered perspective. It has also has taught me to embrace that quality of my own life, because in some ways it is a material expansion of my experience. My identity is so complex, and my work has allowed me to feel affirmed in that complexity. And then there are a lot of other things too - it has taught me how mix paint, about primary colors and how to draw.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

Just as there is emotional sensitivity and visual sensitivity, there is sensitivity to touch. As an artist I operate in the material world, and knowing how materials move and interact with one another is all based on how my hands interact with them. Just through the process of making I have definitely become more sensitive and dexterous than I was before. There is power in the hands. Just as in everything else we are talking about, the hands are art too.

Camille Hoffman in Queens, New York on December 17, 2016. Photographs by Julia Girardoni.