Doug Johnston

Who are you?

I’m Doug Johnston. I’m kind of both an artist and a designer. For the past six or seven years I have been focused on this same process of coiling and stitching rope into all kinds of things; I make objects of various sorts, sculptural and functional, and in various sizes.

How do your sculptural and functional pieces differ?

A lot of times I try to not make the distinction or I try to minimize that boundary. In a way, the pieces I make take cues from both sides. Sometimes I will think of a simple basket, which is functional, as a sculpture in the shape of a basket. That to me is kind of an exciting existence; it happens to live in in both realms at once.

I think that a lot of people in the art world or the design world might not be open to allowing those things to coexist. That has sometimes been a challenge in making work like this and getting it out into the world. They say that something can’t be artwork because it also has a functional aspect, which to me is kind of silly and unfortunate. I see where there are instances like that, but I’ve always been attracted to objects that have that plural existence.

Why rope?

This kind of gets into a whole other side track of how I got into doing this work, but in grad school I made these large pavilion things for my thesis project - it was a collaboration with a classmate. Our work was very different, but we collaborated because we were really interested in each other’s work. We made these big, three-dimensional spaces that were sort of like social spaces woven from flexible plastic tubing. With a little bit of an idea of what the space would be like, we would build a wooden frame to a certain size and then we would start wrapping it with plastic tubing. Everywhere that there was an intersection, we would put a zip tie and tighten it. Once it gets to a certain density, you can take the frame out and you’re left with this free-standing woven structure. In the process of composing the object you are transforming a flexible line of material into three-dimensional space. It’s like an improvisational three-dimensional drawing in a way. I really liked the simplicity of taking that one material and connecting it to itself to create a space.

After grad school I moved to New York and didn’t have room to work on these huge things. I started looking for other related processes that I could do in my apartment. So I got into knitting, which is an even more direct translation of that idea in that you are taking the yarn and making a stitch without even using another material to connect it. It’s so elemental in that way.

Then one day I saw cotton rope in a hardware store down the street. I really liked the natural quality of it because, especially when it is undyed, you can almost see the plant in the material. I liked that this rope had that visual connection to its origin. The texture tells you exactly how it was made; it was braided. That is important to me; that the process of creation is visible and that it forms an image in someone’s mind of a person constructing this thing, or at least it reduces the amount of steps or barriers between them and the origin of the materials.

Rope is also interesting to me because it is one of the oldest human technologies. It is not made as an aesthetic material; it is almost purely utilitarian. There are all of these associations with it. For instance people who grew up sailing and who are into nautical, marine things will be into this rope work that I have been doing. I'm from Oklahoma and I was never around the sea or the ocean, so I never had that association but I totally see it now. There are also associations with survival and adventure. Rope technology has just been an essential tool for humans to become what we have become, and the potential of it has always been exciting to me.

Describe your process.

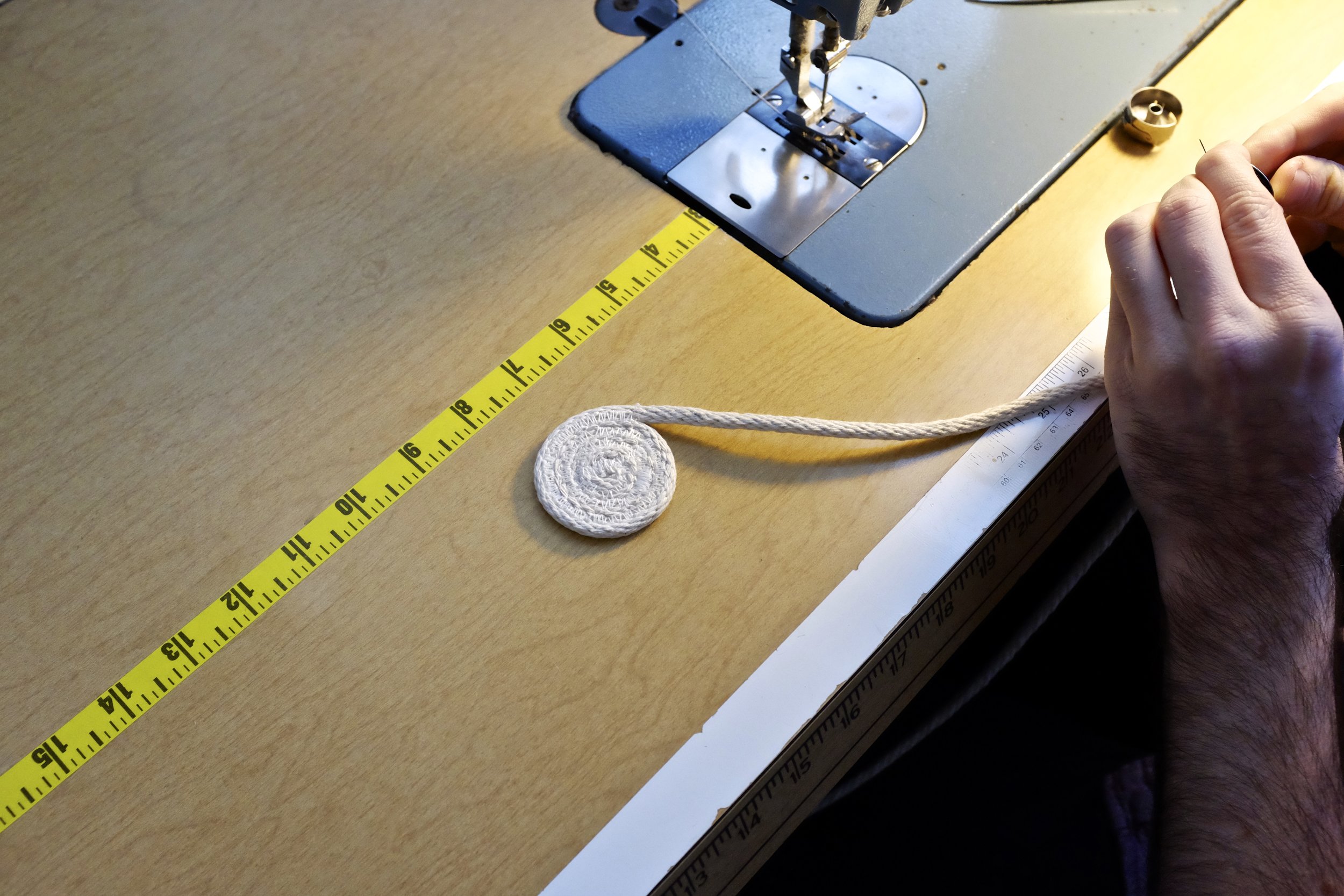

It depends on what kind of thing I am sitting down to work on. For example if it is something for the retail collection, like a basket, the design is already done. In the studio, we don’t have any kind of pattern, mold or form that we use, but what we do have are dimensions. So you know that to make a certain shape, you have to make a base of a specific width and then, once you start sewing the walls, you increase or decrease the diameter to a certain height. Doing that will more or less achieve the shape that you are going for. It is almost like a program or code. You just run through the code and you get this thing that is more or less the same each time. But every one is slightly different, whether it is where the stitches show up or that the shape it has is slightly different.

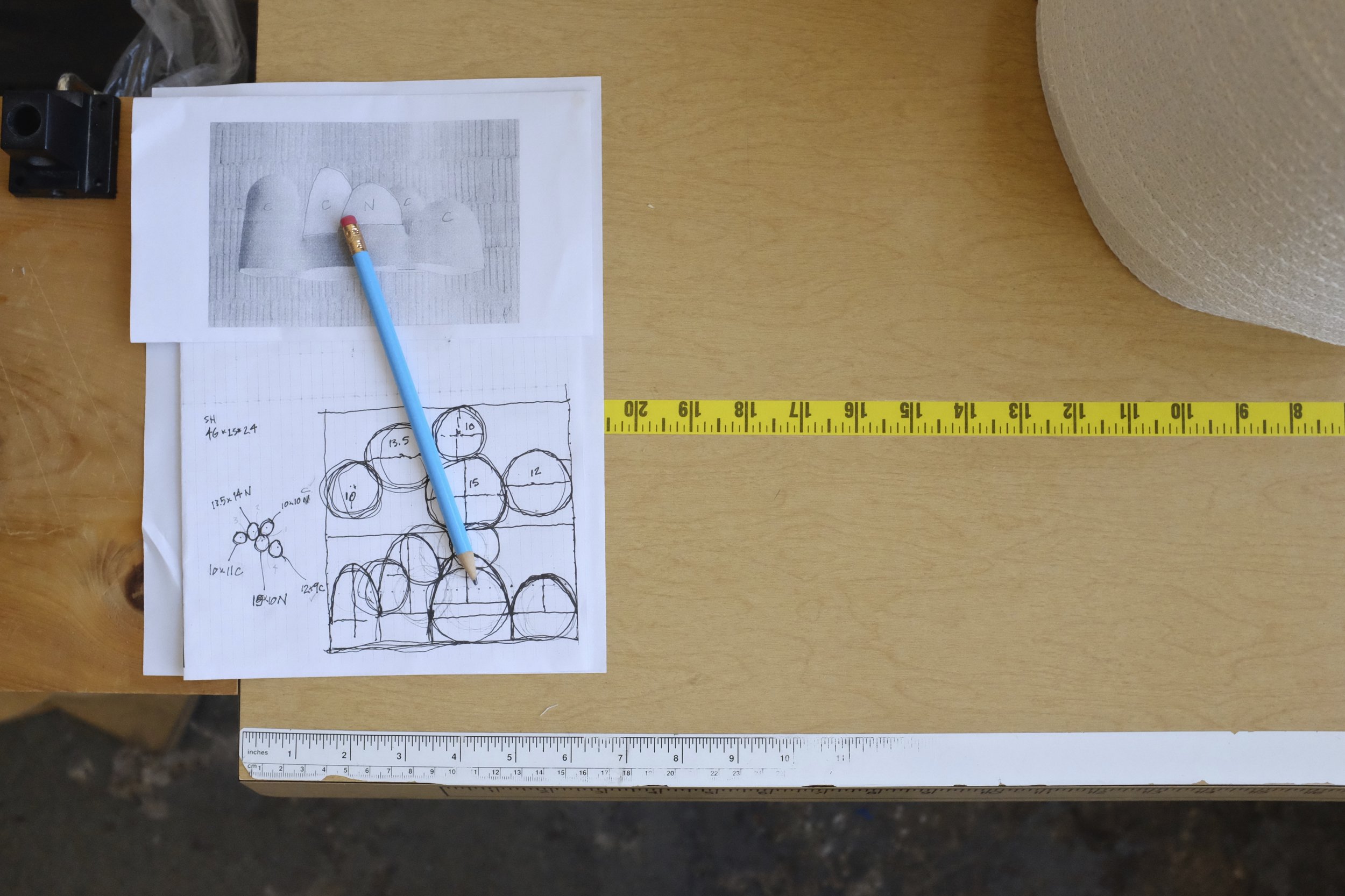

If I’m working on something more sculptural, or working on a new piece, usually I start with sketching. I will either just do some sketches for few days or re-visit something that I sketched years ago. I have this binder with years of sketchbooks that I will just look through. And then I will sit down and sew. Depending on the piece, I will either go directly for the shape in the drawing or use the drawing as a starting point and let it take shape as I go.

For me color has always been a secondary consideration for various reasons. One is that I am more interested in the material itself and its natural color, and the other is that I am partially color blind so I tend to be drawn to colors that I can easily identify. I tend to stick with blues that I know for sure are blues, and the same with red, which means that I have ended up using a lot of primary colors or neutrals. With neutrals it’s not so much about the color as it is about changing the value. I mean that's mostly how I see color - as lighter or darker, warmer or cooler - but if it gets beyond that it gets really hard for me to tell sometimes. So really color is just used to add lightness or darkness. For example when I made this one piece, the most colorful thing hanging on the wall, I didn’t want to have to make any decisions about color so I just randomly used up the leftover bobbins that were sitting in the sewing machine tray. I like that better than having composed every color very carefully; it tells the story of how it was made, and how the studio is set up. I like taking the decision making out of my own hands. I just want to be working and getting the primary things taken care of, so I like to have the secondary things like color already in place. The design of those systems to me takes the place of aesthetic composition choice.

Under what conditions do you work best?

I have been trying to not schedule any exhibitions so that I don’t have deadlines to work under. I'm trying to get back to the way of working that I had when I originally started doing this; no one knew what I was doing and I was making the stuff because I wanted to. When a show is scheduled I have to make all of these things under the constraints of a deadline and under the constraints of expectations. For instance, the gallery I show with primarily is Patrick Parrish Gallery, which is more design oriented. I wouldn’t make a piece for the retail collection and show it at Patrick’s gallery. I would like to be able to do that but the way things have gone there have been constraints applied to the studio work by outside forces. So lately I’ve been trying to get back to that point where there are almost no constraints except for the conceptual ones that I place on the work myself.

How has your practice evolved over time?

The process of coiling and stitching is not one that I invented. I found a tutorial of how to do this on YouTube. I was looking at conventional coiled and stitched basketry from indigenous cultures all around the world, and at first tried hand stitching the traditional way but didn’t have the patience for it. When I was searching for that I stumbled upon videos of people making coiled baskets with sewing machines. What they were doing was taking cordage, wrapping it with fabric as a way to use up fabric scraps, and stitching it with thread that was either clear monofilament, or matched the color of fabric. They called them fabric scrap bowls, so there was no emphasis on underlying structure and materials used to make the basket. But to me, the most interesting part was that they were taking rope and coiling and stitching it with a sewing machine.

I only had colored threads, so I was stitching with those and I really loved that it showed all of the areas where you have to backstitch or where you wobble a little bit in your sewing. In the original process, all of that was hidden. I really wanted the object itself to be a recording of its making. Not just the object itself, but the materials themselves too. So in exposing the cotton rope and by changing the thread color you can really see what happened. The final product is a is a diagram of its own creation. I was always really drawn to that approach because it tells the story of how humans are taking elements from nature and transforming them to their own needs - literally shaping the world around them. So in this work, you can see that someone took cotton, turned it into rope, and then coiled it into this vessel. Again, it's breaking down those barriers between the piece and how it was made. In a much broader sense, it refers to what our history has been on Earth as humans and what role we have had in coming to the situation we are in now. So much of my interest in the work that I make and the materials that I use and the processes are their ability to make that connection. To me, there is the possibility for every little stitch to tie those ideas in. Or, at least, as I am making a piece, those are the kinds of things I am thinking about.

It is really helpful for my ability to see that bigger picture of humans, from making rope a hundred thousand years ago to fifty years from now when the first humans will be walking around on Mars. To me, that is all one story. For example, the coiling process is one of the oldest forms of vessel making, but it is also how 3D printing works. Technology is utilizing these ancient things and it tells us so much about who we are. I think that those lessons are so embedded in materials and objects. So that is the bigger picture of the work that surrounds everything I make.

How has your experience working in other media informed your current practice?

Pragmatically, there have been a lot of ways that lessons I learned from my experience in architecture pop up all the time. When I first started working with rope, I would think of the pieces as little mini buildings or spaces. That is one of the reasons that I started making these conjoined forms, which in a sense is what a lot of architecture is; shaping space and creating a flow of space.

I also used to play a lot of music and music to me had such a physical presence. A lot of my work in undergrad was trying to make connections between architecture and music, which a lot of people have done. I eventually got really into playing the drums, which is a very physical thing; you are really moving in space a lot compared to other instruments. The type of music that I was playing was more improvisational. You start with a loose idea of what you want to play and then the music is composed as you are playing it. So a lot of the way that I work, especially with the more sculptural pieces, kind of captures that same idea. I will start with a loose idea of where I want to go with a piece, but as I am sewing something will happen and I will go in another direction. That is where it gets really exciting to me. I even refer to it as listening to the piece. As a drummer that was a skill that I had to develop quite a bit, but that was the most fun thing about playing music, and the most exciting thing about it.

I also used to do a lot of photography, which has been really helpful in presenting the rope work. Knowing how to use a camera, how to light stuff, and how to process a photo in Lightroom are all basic skills that you just have to know as an artist.

So in a way all of those different things that I have done have accumulated. One of the reasons that I have stuck with this coiling process for so long is because it was able to synthesize so many of the things that I was doing into one practice. Before I was always conflicted. I really loved music and I really loved photography and I really loved architecture. I loved all of these things but it was like I was trying to drive five cars down the highway at once. I would have to drive one a little bit, then get out and walk back over to the other one and drive it. This was like finally having just one car.

What is the most challenging part of your process? Where do you find the most ease?

It is kind of different every day. It sort of depends on my mood and what is going on that day - or the election or something. There are so many factors. What’s been challenging is figuring out how to contend with those outside forces I talked about; it has been difficult to minimize their effect on what I make and what I want to make. I try to strip away those layers and really stay focused on the core ideas and the bigger picture of what I want to be doing. The more people are seeing your work and the more of it leaves the studio, the more feedback you get. And that is a lot of information to take in and to manage and to process. So for me the biggest challenge has been to try to determine how much to take into consideration all of those outside values, because a lot of it is really useful feedback and input and so much of it determines your practice in reality - it’s not stuff you can ignore. So you have to consider it but you also have to balance that with just your feeling and what you want to do. Even if you show something in an exhibition, people can go look at it but there are so many other factors that influence it, like the reputation of the gallery or what type of press looks at the exhibitions from that gallery, or here in New York, even what neighborhood the gallery is in. So much of that you can’t control, it just sort of is what it is. In the end you just want people to look at the work and to a certain degree you hope that they can see in it what you see in it as the maker, but it is always interesting to hear other things, like I was saying about the nautical connections I never saw. I don’t know if that has necessarily changed what I do but it definitely opened my eyes to the fact that these things have a whole life once they are finished - they are kind of like kids in a way.

But really, I am always hoping to run into challenges or limitations. I am the kind of person who gets excited about challenges and learning why they are there and seeing what other people have done when they face similar issues. I feel like it’s a good sign when you find a new limitation because it means that you are really pushing up against things. If you’re not finding them it is a good sign that maybe you are stuck your comfort zone a little bit too much.

Is there anyone or anything that inspires you?

I am always looking at art and design and architecture. Also my wife and I love going to natural history museums. In Osaka, where she is from, there is The National Museum of Ethnology, which has artifacts from all of global history. So in a way it is this survey of human production. That is really fascinating to me. The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan is kind of the same way, but it is more focused on industrial production. Henry Ford just started collecting stuff that used industrial processes and now there is this enormous museum to showcase it all. It’s pretty mind blowing. They have cars, and sewing machines, and lightbulb making machines. They have building technologies - they have one of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Houses. They have locomotives. They just have everything. Those kinds of things are really exciting to go see just in terms of the wide variety of things that people have made. If you look at a car through the filter of artist's glasses for instance, you see that yes it is a car but also it is a product of culture and because of that it has affected and changed culture in many ways. So we love going to museums like that; you just start to get a sense of the bigger picture I suppose.

What has your practice taught you?

I think that we have tried to set up our practice on our own terms. With every little business decision that comes up, my wife, Tomoe, and I probably think about it more than we need to, but we try to see it almost like a design opportunity. For example as a precedent for our practice we looked at the Shaker community and how they existed in early America as this utopian community interacting with an outside world by making all of these objects. So we almost like to look at our practice like a little utopian community in this room instead of looking at it as a business. We will look at what other businesses do, but we don’t take that to be what we need to do. We only do what makes the most sense for us. It takes longer to do that, and it is definitely not the most profitable way of working, but in the end I think that we have learned that the practice itself is part of the work. We could have taken so many different directions and probably gotten more exposure or grown the studio or made more money, but we really wanted to work in a certain way. We weren’t really clear on that at first but it developed by going through all of these different situations and looking at every one as an opportunity to define our practice and learn about our place in the world. We feel pretty good. The whole thing is a huge learning experience in a way. We are really set on doing it all ourselves and we really want it to be an organic path through time and through the work. So it is hard to say any specific lessons because it’s almost like the whole thing is one big life course or education.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

I have specific calluses from where I hold the material, on my index finger and on my middle finger. And then on my thumb, probably more so some days than others depending on whether or not I am applying a lot of pressure while I am sewing, there is a zone that will almost have an indentation for a couple of days because the rope is just constantly rubbing on it. I personally have never sewn through my finger but I am the only one in the studio that hasn’t. The first one was our assistant and that was really scary; I had to help her remove a thread from her finger. But my hands have not been shaped by the needle in that way. I mean we do get cut, I have a few little nicks from the needle and from other stuff. But it’s never been that bad.

There is also what they call muscle memory. I listened to that Malcom Gladwell book where he talks about the ten thousand hour theory and I realized sometime last year that I probably got to that ten thousand hour point in doing this process. It just feels so normal and natural now, it’s like my hands just know what to do.

Doug Johnston in Brooklyn, New York on October 29, 2016. Photographs by Julia Girardoni.