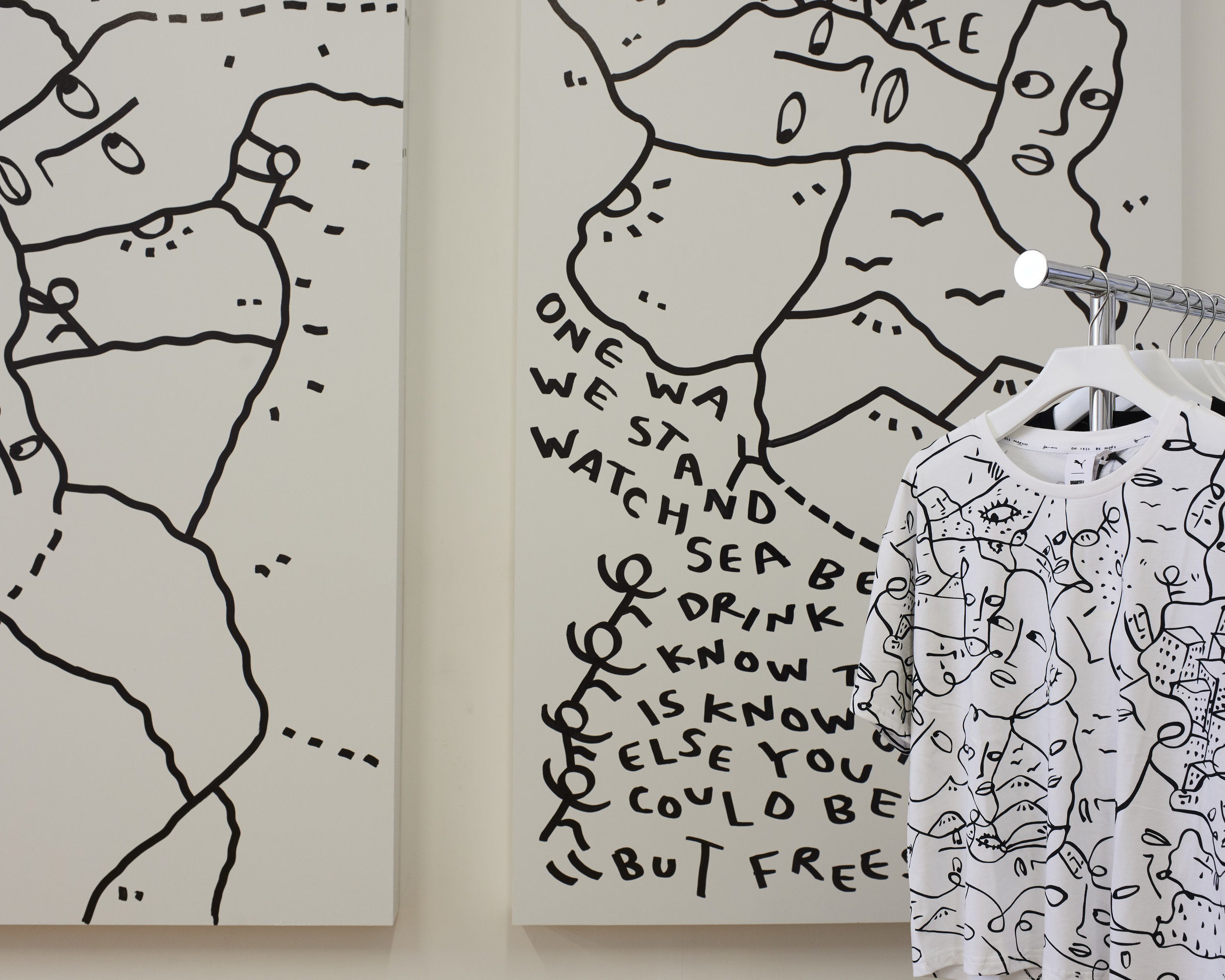

Shantell Martin

Who are you?

It’s a question I think a lot about and a question that I find difficult to answer. At the end of the day, I’m this girl from Southeast London who has found a gift in drawing and line work. I’m a curious, interesting person who loves to create marks and lines and experience and performance. I enjoy being vulnerable and honest and I’m always trying to be a better version of myself. Through my work I put a mirror out there to ask other people the question Who are you? in hopes that I’ll find more of a vocabulary to answer the question myself.

What do you make?

I make many things but the foundation is typically lines or drawing. And that can go from digital visuals in clubs to analog visuals in performance to technical work in code to simple line drawings. I'm not a performer but I've ended up creating 99% of my work live with an audience because I think process is so important and we don't share it enough.

Why lines?

Why not lines? I think lines are the most fundamental way that we get to extract and see ourselves. They’re something that we are all inclined to naturally make as children and something that we gravitate towards as human beings. There’s something really special about our own lines; to really get to know yourself through line is a great path that a lot of us don’t give ourselves the luxury to go down. Lines are for everyone. Lines are the most accessible, stripped down version of yourself. Everyone has their own unique line, but it takes a little bit of mining to extract it. Lines are so simple but they have layers of complexity that reflect you and look like you and feel like you and sound like you; lines can be music, they can be dance, they can be drawing, they can take many forms and mediums. It takes a ton of work and practice to get to the point when a line is a true reflection of yourself.

Do you have a preferred drawing tool?

I don’t have a preferred drawing tool, but right now I gravitate towards three types of markers. One is a Staedtler Lumocolor m-size permanent pen, one is a Krink K-571, and there’s also a Sakura 0.05—a really, really fine marker. When I was in Japan three weeks ago I actually found a 0.03, which is super, super fine. But the Sakura 0.05, the Staedtler Lumocolor m-size permanent pen, and the Krink K-571 are my usual suspects. I’m not a huge fan of pencils because you have the possibility to erase them. I think pencils allow people to hesitate and be insecure. When you work with markers you have to tackle things head-on and confidently without hesitation because it has to work.

I'm very confident with line and I'm very familiar with my line—we have a really good repor with each other and we know each other quite well. When I was doing a residency at Autodesk in San Francisco I had access to 3D printers and design and all these types of manufacturing technologies. I was thinking about what I could do that would really make a difference in my practice. I thought about the simplest thing that I could do that would also have the most profound change on my output, and that was simply to go from one line—this very familiar, comfortable line—to multiple lines or multiple thicknesses of lines. So I 3D designed and printed these building blocks. For example there's one where you put two markers into it so that you can draw with two lines as one line. They could be multiple colors, they could be black; it doesn't matter. You go to draw the way that you usually draw because that's your starting point, but then when there are two lines you realize instantaneously that some things don't work. You have to live iterate what works and what doesn't work through the practice of learning as you go. It’s a really nice way to completely unknow yourself and find yourself through the practice of doing.

What are the freedoms and limitations of working only in black pen?

The thing is I don’t only work in black pen. I had open studios the other day and a girl asked me this question. She said something along the lines of, "Are you comfortable doing the same thing all the time?" It was a weird question because it implies that you don't change. It implies that you're not progressing and that you're stuck with something. I answered and was like, "As an artist you're in search of your own fingerprint for your identity and your style, so if you've found that then why would you force it to change?" The thing about my work and a lot of artists' work is that you end up with something that's quite recognizable. But that's just the tip of the iceberg. If you start to look beyond that, you'll start to see that there's color and there are different materials and there's a history there.

I've been using this line and I've been doing these types of faces for about three or four years, and in the lifespan of an artist that's a really short about of time. I started my career in clubs in Japan doing live visuals to dancers and musicians and DJs, and there was color—it was all colorful. In a way that's because those people brought the color. And there were other projects with color; for ten or fifteen years I collaborated with my grandmother and we would create these needlepoint pieces with color. I did a show this year in January at Northeastern University in the gallery on campus and it was a whole colorful piece. So there isn't an absence of color, it's just a preference of black and white. And it's a preference because of the many benefits, like you know that you can’t hide and the line has to be good. I love that color can be easy but black and white is not. Black and white doesn't dictate where people should look; people are drawn to different things. There’s a calmness to it that you sometimes don’t get with color. But I don't think there's an absence of color in my work; the pieces have so much movement, and with that you see color. It feels colorful, it feels bright, yet it's not. Color can have different depths and meanings.

Describe your studio.

My studio is very organized. It's quite black and white. Right now I have my table installation in the middle, which will be here for a couple more weeks. There are a lot of panels and canvases on the walls and some files and drawings in the back. That’s about it, really. I'm semi-organized at the moment; there are things standing out that need to get done. Since I was a kid, people would come to my house and be like, "Woah your room is so clean and organized." I was like, "Well what did you think it would be like?" There’s always been this weird misconception that my space would be messy—maybe there’s something seemingly messy about me, I don’t know.

Under what conditions do you work best?

I'm a huge procrastinator so I don't like a lot of time for projects. When you have that time, you think too much, you hesitate, you plan, you doubt. I prefer to work with an audience because if there's an audience watching me draw, I go for the most vulnerable, honest decisions since there's no time to do anything else. So short time constraints with an audience, maybe with some nice music.

Do you have any rituals surrounding your practice?

I work on a lot of larger drawings and murals, and I didn't notice it before but someone pointed out to me that before I start drawing I'll pace up and down by the space or the wall. Someone asked me, "Do you think you're measuring the space with yourself before you create the piece?" That made so much sense to me; if you're not planning the piece, the composition or the content, you must have a clear understanding of the space and the structure from a different perspective, and that perspective is physical. So I've noticed that a ritual is to pace a space—it's almost like winding up a clock within myself before I start. And then with the smaller pieces I very rarely work by myself, but if I do I'll make tea, I'll listen to something like a podcast to distract me from thinking, and then I'll draw.

Describe your process.

You put yourself in an honest, vulnerable position and you create your work. Depending on what the project is—it could be music, it could be drawing—I might think about some key words or themes. I'll write those down to kind of soak them up, and then I'll have them as ammunition when I work live. A lot of the work is spontaneous and intuitive, but it can be fed as well; you can feed it things so that when you create you draw from recent readings or recent words.

What role do words and messages play in your work?

I see words and phrases and messages as seeds. They're the seeds that I plant throughout my work. From a sticker that I give someone that says Are You You to murals that say there's no one else I can be or you watch too much TV, there are seeds hidden throughout the work. Their job is to be digested by the viewer and to grow. People may consciously or subconsciously see them, or they don't see them at all, but the chances are that they get a connection to those seeds and they grow and they have some form of positive impact. Or at least just create a question. Artists are like trees and trees have seeds. It's all about finding the best way to get those seeds out into the world to spread their messages, be it on a product, be it in art, be it in a performance, be it in whatever form.

In what ways do collaboration and education play parts in your process?

These are two things that I always encourage and push. Collaboration with artists is important, but it's especially important with people from different industries. We're stuck in the idea that art should be here and science should be there and finance should be somewhere else. If we didn't build walls between these industries we would collaborate between mediums. And the more that we collaborate between ourselves as artists and the more we collaborate with people from different industries, the more we can expand and grow and create. Everyone benefits. I'm also a huge advocate of collaboration versus competition. I think a lot of artists are very shy or cautious to collaborate because they feel like they're in competition, which I think is absurd. But that just depends on your experience and where you're coming from.

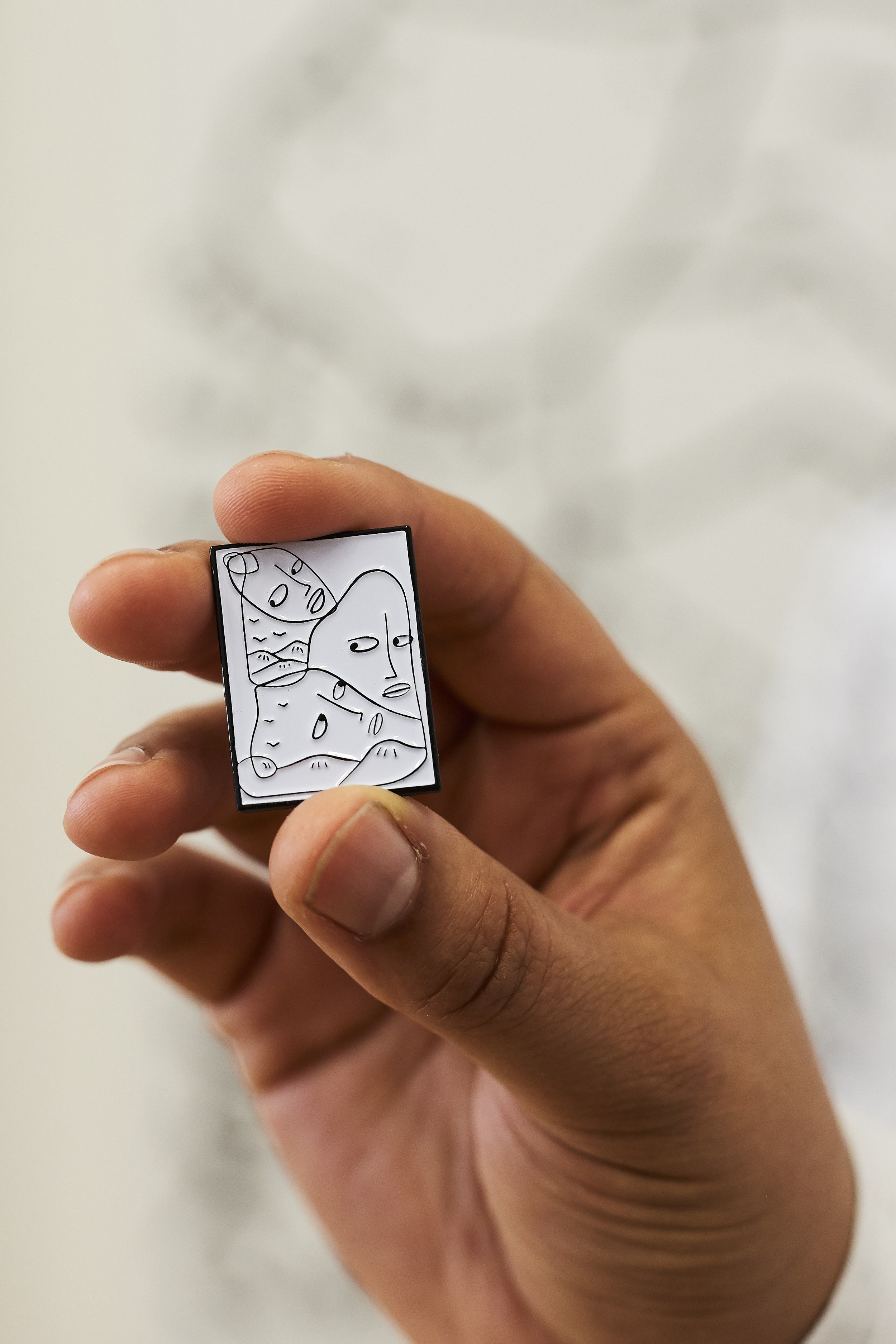

And then education. Education needs to be rethought from all perspectives. I feel like artists and audiences and the world of art need to be reeducated on how to support artists. We have a system that is a facade; it looks like it protects and supports artists, but it actually doesn't. It profits from them. Even if you go back to art schools, they don't enable artists to be self-sufficient or self-educated. You have an infrastructure and an industry that doesn't actually support artists; it profits from them. And then you have an audience that isn't aware about how to support artists. There are actually many ways in which you can support artists. You don't need to buy a seventy thousand dollar painting, you can buy a pin or a sticker.

What is the most challenging part of your process? Where do you find the most ease?

The challenging thing is that more and more often I take on bigger and bigger projects—like physically bigger. Someone described me as a drawing gladiator and I realized how true that is. I like to create and get it all out as much as possible; I'll do an eight thousand square foot drawing in three days. It feels more honest if I can get it out and just do it, but then because it's so physically challenging it will take me two weeks to recover. So that's quite challenging but it's also quite rewarding. It's like when you draw really, really fine. You take on a huge piece of paper and when you start you think you're never going to finish, but you're committed, and when you get to the end it's so rewarding because you completed it. So there's that juxtaposition of something being really frustrating and really rewarding at the same time. Feeling like you’ll never get there but you do.

What do you hope your work communicates?

I hope that the work communicates a very fresh, fun, playful, minimal viewpoint on life that has positive values and those seeds that I mentioned earlier. But most of all I hope it makes people smile.

In what ways has your practice evolved over time?

From a physical standpoint it's definitely less detailed now. It’s less dark, it’s less helpless. In a way it has gone from this very dark, helpless, depressive, uncertain place to a very light, whimsical, more confident place. So there’s been an evolution and a growth there.

What has your practice taught you?

Your practice teaches you about yourself. And art, as cheesy as it is, is about self exploration. You have the real benefit of getting to know yourself over and over and over again. There's a sense of self security that comes with that, which is invaluable. It also teaches you that you’re always changing. You almost can't relate to the person who created the work that you did five or ten years ago, even though you can recognize that it's yours, because you're not them anymore. So you have these constant reminders of distant versions of yourself.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

I don’t know... Has it shaped my hands? I think my hands have been the same since I was a kid.

Shantell Martin in Jersey City, New Jersey on May 4, 2018. Photographs by William Jess Laird.