Michele Quan

Who are you?

I’m Michele Quan. I’m from Vancouver originally. I moved here in 1984 to go to Parsons, which I dropped out of after a year and a half. I was a jewelry designer for twelve years. Now I don’t really call myself anything. I don’t call myself an artist, because when I think of art I think of fine art. I don’t think of myself as a sculptor or as a designer either. I think my work is a little bit of everything. You could say I’m a ceramicist, that is probably the closest thing.

How did you begin your ceramic practice?

I took a class in 1991 and I really loved it. Then after doing jewelry for twelve years, I took another ceramics class. I used that class as an outlet to make something without any boundaries. I wanted to go and do pinch pots every Saturday and sit there and work with my hands with no constrictions, mental or otherwise. Shortly after I did that I had my daughter and left my business. About a year and a half later I realized that I needed to do something beyond just being a mother. I was going back and forth between a bunch of different things, one of them being ceramics.

Describe your workspace.

I call it the princess studio because it has heat and air conditioning and a drain in the floor. My last studio had no air conditioning, no heat, and the sink was downstairs. The guy who owned the building always had his fork lift out and it smelt terrible, like gas. I called it ‘Macho Studios,’ it was kind of a rough studio. But I loved it. I was there for three years and then I moved here and it felt like a princess studio. It’s comfortable, clean, organized and quiet. I love this studio. I like coming here every day.

I have things on the wall that I connect with somehow. When I went to the Yoko Ono show at MoMA, I got that poster. When I first saw it, I read “War is Over.” I thought, it is not! I wanted to push back. But then when I read that second line, “If you want it,” a lightbulb went off in my head. It’s not about war, it means you can do anything if you really want to make it happen. I had to get that poster.

Under what conditions do you work best?

I like my studio to be organized, for like-minded things to be together. I like things that are almost dry to be in one area, things that are totally dry to be in another area, things that need to be painted in another area. Then I like things organized by style and by shape. So I like a loose sense of order. But I’m not totally neurotic and crazy - I can kind of let it go for a while. Then sometimes I get here earlier than everyone else does and spend time moving things. I call it the ‘MSA Department’: moving shit around. I’m always moving things, because in ceramics you have so many different stages. It’s nice to keep it moving. Studios can get really cluttered because you need so many tools and supplies. So for me I need it to be somewhat organized. I call it my Sesame Street organization. It’s kind of like, which one doesn’t belong? Everything has to belong to its own group. So I spend time doing that and it’s how I work best.

I also like limits, I do. I’ve always thought that directors, not across the board but generally, do really good and inspired work when they have a set of limits to work within. If it’s too open, anything is possible. Whereas if you only have so much, you have to stretch it out. You kind of do the best with what you have. I like that. It’s kind of a spirit thing. I think you have to go into the well and pull out the spirit of something, then figure out how to translate that in a simple way. You have to dig deeper, you have to be resourceful. That that can be a really great thing - it has only served me well, that’s for sure.

Do you have any rituals surrounding your practice?

Usually I work on my to-do list. That sets me up mentally. I have a program called ‘Wonder List.’ In it I create a running list of all the things I want to do, then give them dates. Then when I get to the studio I tend to organize a little bit. I never just dive in, unless I’m so busy that I have to. A lot of the time I am organizing for people, helping to keep the momentum and flow.

Describe your process.

When making things I have to see it in my head first. Some people just go for it and it evolves, but for me it’s weird - I have to see it in my head or I don’t believe I can do it. I have to be able to see the process linearly. Once I figure out how to make something the first time I’ll make a template so that I don’t have to re-think it every time. If you have to think too hard it’s more exhausting. I have production books, which I’m working on right now. The books give you space to use your brain for other things. They tell you things like what size template to use and how thick the slab should be. A lot of my processes start with slabs, even things that are round. I have some things that are wheel thrown; all the bells are on the wheel, the planters are on the wheel and the little dishes are on the wheel. I think the piece tells you what needs to be done. I think you just know.

In ceramics there are windows of time that you have to work within. After one step you have to wait for the next. These discs, for example, were rolled out yesterday, given their first cut and sandwiched between two boards so that they could set. Now I’m doing the final cut and then they’ll go back in between boards. By tomorrow or Monday I’ll put holes in them and stamp them. It’s a matter of timing; of keeping on top of all the steps. And patience.

What’s the most challenging part of your process? Where do you find the most ease?

I am challenged the most when things go wrong. For example I’ll make something and it comes out perfectly. Then I’ll replicate it and it comes out fine. But once I put it into production and make it a bunch, something goes wrong even though the process was exactly the same. The wildcard situations are the most challenging thing. People order things specific things from me; what they see is what they want to get. So I try to eliminate wild cards, like this glaze called shino glaze. It’s a very famous Japanese glaze and it’s beautiful but kind of a wild card. It varies every time you shoot it, ranging from a deep reddish rusty color to an iridescent gold. While to one person that wild card might be the most beautiful thing in the world, I don’t want that kind of inconsistency because I want to be able to reproduce things.

I think that design is an organic thing. One thing leads to another - it’s a kind of momentum.

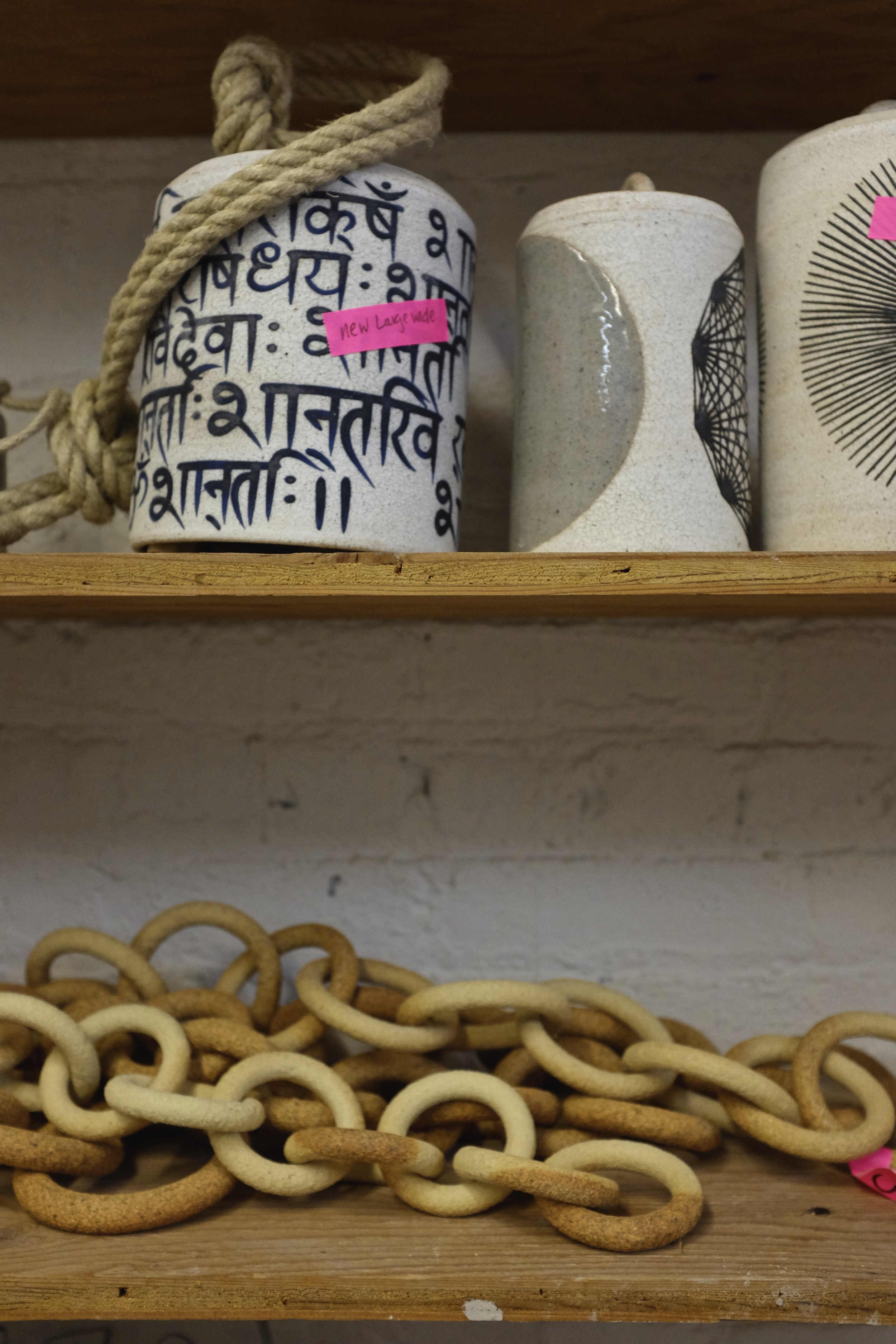

How does your work engage with eastern iconography? What drew you to those symbols originally?

In my early twenties I started to read a lot of different types of eastern philosophy books - Buddhist, Hindu, Zen, all kinds of stuff. I was just checking it out, then it kind of continued. Tibetan and Indian art are full of symbols. They all mean something, they all relate to ideas. Early on, I remember learning about Chinese symbols and incorporating them into jewelry. Each character is like a small poem. That was super inspiring. So it started back then and it has been a continuous thread that I just keep drawing upon. I am constantly pulling and reading and learning - it just gets deeper.

What do you hope that your creations will bring into your customer’s lives?

I’m not making work to challenge people. I just hope that at a moment in their life, customers could have pleasure from looking at or owning an object that I made. I feel like anything I say is going to sound corny, but I want my pieces to create moments where people look back at their intentions and how they want to operate in the world, what they wish to see or have or be or connect with. Just bringing them back into the present and connecting them to the beauty of the world; that’s a moment where everyone feels really good. It’s like touching ground before you go off into the craziness.

How have you learned what you know? Did you have any teachers or mentors who helped shape you as an artist?

I think you get shaped everywhere you go. It could be a from book, a person, a teacher, an environment. In terms of ceramics, I took this class for a year at Third Avenue Clay and I learned stuff through Adrienne Yurick, she was great. After that I went to Greenwich House, it’s a three-story brown house that started as a settlement house at the turn of the century. I took classes there and there were all these people who’d been living in New York since probably the 30s, 40s and 50s - they’d been going there forever. Everyone was so generous with helping me, nobody was hiding.

In what ways has your practice evolved over time?

It’s definitely evolved. The other day, somebody said to me, “It’s changed since you’ve been in this studio.” In a good way though; they were being positive. My first thought was really? It feels the same! I feel the same! I guess it’s because I’ve grown a little bit and there are a lot of different things being made. I think things happen on such a slow progression, it’s not like I woke up and was somebody else the next day. I’m still me, but things change. One thing that changed is that now I’m more of an orchestrator rather than sitting around and making things all day. I think I’ve had to be a little bit more conscious of business and selling. My admin life has grown because the business side has grown bigger.

What role does commodification play in your work?

I did jewelry for 12 years so commodification was definitely a part of the business. I did it with a partner, a good friend of mine, so it started out of love and out of being totally inspired. Then it became a business. I was in a groove where I could do a trade show and people could buy my work, then I could go back into the studio and make the things that I needed to make. I think it was just a comfort zone.

When I first started doing clay, I was just making things and it was great. I remember being at my old studio making these whale tusks and having the thought that I just wanted to keep doing ceramics. Eventually it came to the point where I need to question How am I going to get it out there? Do I deal with decorative art galleries? Do I deal with the art world? I just couldn’t wrap my head around it. I could have gone the art world route and pushed the boundaries, but I didn’t. I was making garlands for three years and kept coming up against a brick wall, thinking Where am I going with this? Who wants these? They were expensive and I didn’t want to tell people what they were because they were too loaded with symbols. I loved the garlands, but I didn’t want to talk about them and I didn’t want to sell them. The floodgates opened when I started making bells. They were also loaded with a lot of ideas and preconceptions, but they were more accessible. More people could understand them. Unlike the garlands, which were these big things that would cost thousands of dollars, the bells were objects that wouldn’t take over your house, you could just have them right there. They were smaller and more attainable. They felt more commodifiable. So the hardest part was finding the entry to get momentum, to get the ball rolling down the hill and to figure out what direction to push it in. Once you figure out where you want to go, it is just about gathering steam and being open to the flow but also being discerning.

What has ceramics taught you?

I think it has taught me patience and to let go a little bit. That I’ve definitely gotten better at. When I was doing my first installation in Vancouver, I made these garlands of beads that were all strung together. They were painted directionally with a defined up and down. When I hung them I was getting myself all worked up about everything facing the correct way. One of the curators said to me, “Don’t even think about that. Just let it be, let it live the way it lives.” I’ve always remembered that, to just let it live as it is, to just let it be. I’ve definitely had moments where I think things have to be exactly one way and I can’t sway at all. I think people are going to be disappointed, but actually people don’t really see those things at all.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

That’s a hard one. I’ll tell you one thing, I hated this advice when it was given to me: keep it simple stupid. It made me so angry. It took me forever to understand it, but I think that I finally kind of get it a little now. It’s easy to make things really overcomplicated but I have to remember to keep it simple and take baby steps. Beyond that, I try to remember not to get lost in the meyer of spinning my wheels about what I’m doing and what other people are going to think of it.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

Oh. It’s like memory with my hands. For example when I pick up this bell I’m doing so many different things. I’m not just picking it up. I’m conscious of the way I am picking up the clay because things can break and there are a lot of weak points. It’s all about gravity, which I acknowledge with my hands without realizing that I’m doing it. When you’re trying to show someone how to work with clay, there are things that you’re doing that you don’t even remember to tell people because you innately know them from memory. Your hands know where to push and where to pull. I think of it as a layer cake of information, you just keep building and building and you don’t even know what’s sandwiched in there.

Michele Quan in Brooklyn, New York on September 30, 2016. Photographs by Julia Girardoni.