Joseph Vidich & Kira DePaola

Who are you?

Joseph: I guess there are two introductions; there’s the Kin & Company introduction and then the individual introductions. The introduction of Kin & Company is that we’re a family business. We’re cousins who work together to design and build furniture. I think a big strength that we use to our advantage is the constant support that we give to each other. It’s not just Kira and I; there are other family members who are in the business too. Personally, I’m an artist, designer, and architect who has gone through several iterations of how my creative process manifests. Furniture was one iteration that was always in the back of my mind. It feels like it has the most potential to combine all of my interests since it’s something that can be artistic in a sculptural way and it’s also something that allows for a lot of experimentation within the strict requirement that you know it has to function.

Kira: All of what Joseph said minus the architecture part and add in interior designer. I think that furniture is the place where I feel most at home. And if I can get a little smushy about it, working with Joe is also where I feel most at home. Starting your own business and putting your creative output into the world feels risky, so there’s a real sense of security from being in a partnership and being family.

What do you make?

J: We make contemporary furniture that’s conceptually focused and has real attention to detail and material.

K: I think it also really prioritizes social engagement with its users, whether it be the users with each other or with a piece of furniture. We like to bring people into the present so we’re always thinking about what we can to do draw someone in, make them curious, surprise them...

J: Make them engage.

What was the impetus behind founding Kin & Company?

K: It was actually Joe’s mom’s idea. We were both doing creative things separately on the design side—I’d started an interior design business and Joe had been working in architecture after grad school. His mom was babysitting my daughter at the time, so we were fully family-integrated. She thought it’d be cool if we collaborated on something, just a one-off kind of thing, and I suggested that we start a business together instead. So I called him up, we started talking about it, and he thought it was a great idea.

J: I’d been working at an architecture firm, teaching architecture, which I’m still doing, and I was also in a company with two friends from grad school. We made large-scale installations that involved a lot of digital fabrication technology. That partnership wasn’t really working, so it began to dissolve. Then Todd Fouser from FACE Design, who I’d worked for years before, called me up and said that he knew I was looking to do some new projects and that there was a studio space available. So Kira and I looked at it and it was obvious that it would be a great space. Then my other company officially dissolved, I quit my job at the firm, and we started Kin & Company. This was all in the beginning of 2012. At that point we weren’t clearly a furniture design company. We were thinking about doing a lot of things like architectural metalwork, interior design, and custom projects, so it was going in all of these different directions. But the impetus was to have a company together based on our mutual design aesthetics. And now we have a business that’s been established over the past five years. We really consider this year to be the first year of the business in its truest form because we wholeheartedly dedicated the company to furniture design and manufacturing.

K: Everything that happened up until now was getting the ball rolling, just us growing up. And now we’re here and we’re ready to do it.

Describe your studio.

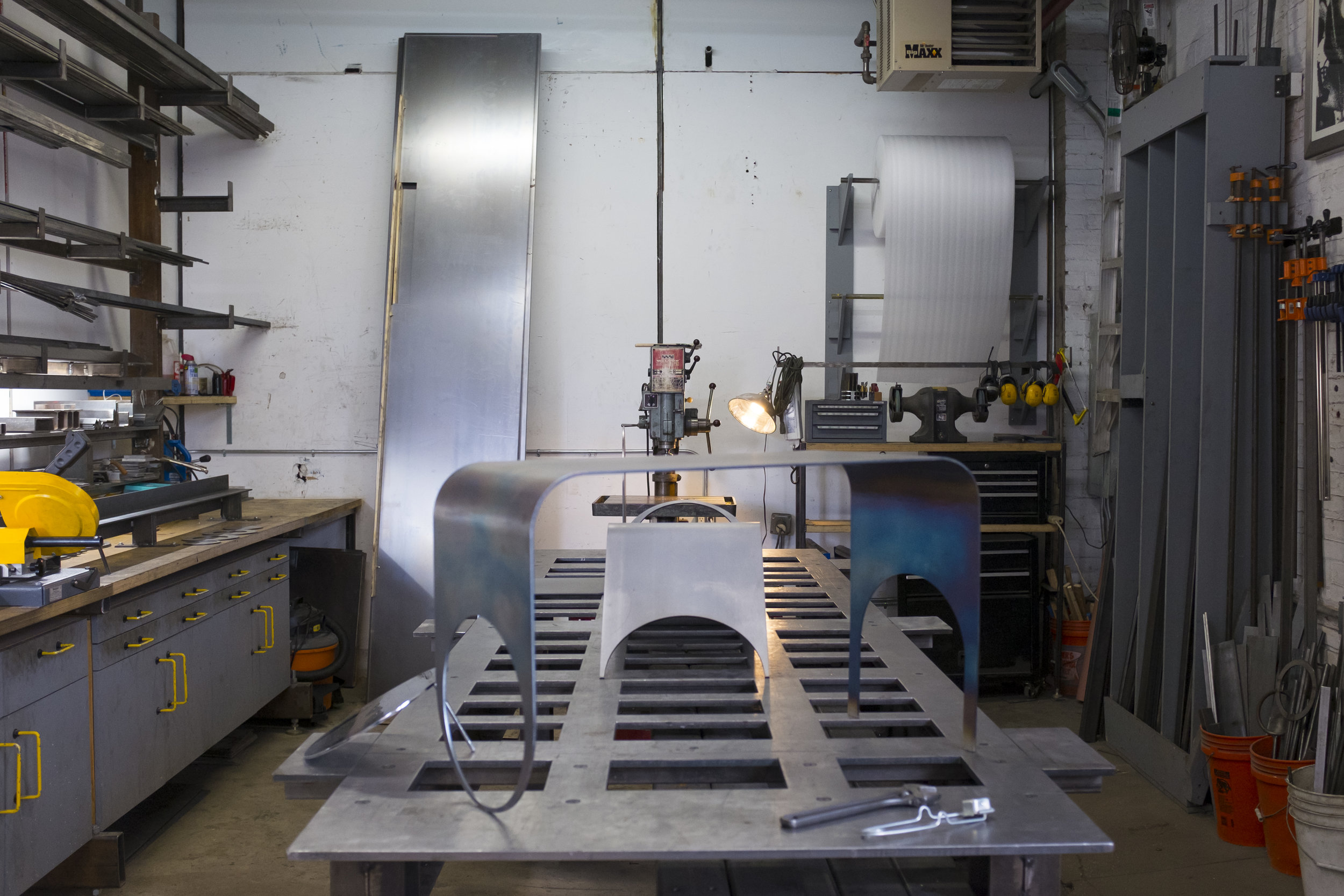

J: The studio is a space for design, a space for making, and a space for experimentation. It really oscillates between all three of those, and sometimes all three overlap depending on what phase of a project we’re in. Sometimes it’s a design space for drawing, using computers, and thinking. Other times it’s an experimental zone where we play with materials. Other times it’s a full-on assembly zone where we put the computers away and manufacture and it’s messy and dirty.

K: In the future, as the business grows, we may just fabricate prototypes there or just do our design exploration there. It may become less of a fabrication space and more exclusively a design space.

Under what conditions do you work best?

K: In the design phase there are so many parts. There are times when I want to talk back and forth and collaborate, times when I sketch, times when I just think, times when I need to be alone and focused. I need the full breadth of those experiences to work best.

J: I think that we work very well in a back and forth when we come together at key moments to discuss progress in terms of design. We’ll work together at the early phases when we’re conceptualizing a new idea, then I’ll break away and work on my own to flush out the idea a little bit further. I’ll start to develop some designs and then we come back together. So we’ll break apart and not speak for several days, and I know that Kira is in her zone doing her thing. As a company we work well in these intense moments together and then in these moments of giving ourselves space to focus.

Do you have any rituals surrounding your practice?

K: Overall I’d say that I’m not very ritualistic. I don’t prep myself for creation that much in any way—maybe I should though.

J: Yeah, I don’t particularly have rituals either. The closest thing I’d say is that there’s a different headspace in going from task to task, depending on whether we’re doing heavy amounts of fabrication or developing new designs or researching. So there’s a ritual per se in the cleansing of the mind to transition between those spaces and get the best focus. I also can’t do anything unless I have some coffee in the morning—that’s a pretty legit ritual.

K: I’m enjoying imagining my best version of how I’d like to create. I could do a ritual that sets me up for success every day. I love to make lists. I don’t write them in a ritualistic way, but I could. I usually feel way more ready for my creative journey or just to get shit done if I’ve made a list. It gets your head straight. I want to take that and make it a habitual ritual.

Describe your creative process.

K: In the conception period we always start with an inspiration point, but it can vary widely. It could be that we want to work with bent steel or sheet metal or that we want to do something with circles or that we want to make something super interactive. It could be material based, finish based, shape based, or concept based. And then we start playing around with the idea back and forth. There’s definitely a collaboration right at the beginning. Usually we come to some point where the idea becomes the kernel; it’s what we’re working with. Then Joe goes home, he comes back and says that he hates the idea and that he started over with a new kernel that has something to do with the one before but isn’t totally related. It’s like the first kernel is the first draft and then he goes home and rewrites the paper.

J: Kira’s totally right—what often happens is that we dive in together to develop an initial seed and then it metastasizes. What happens is that I spend a lot of time sketching by hand and then I quickly move into 3D modeling software. I start assigning material and develop something spatially. As I do that I look back at other inspiration, whether it’s imagery or earlier work or ideas, and then the model will go through these intense iterative processes. There will be fifty different versions of a model iterated and they’ll be on some kind of weird grid that I’ve established with side tracks going down to different paths.

K: It’s like choose your own adventure. And eventually we get to a phase where we say let’s prototype it or play with this element in real life.

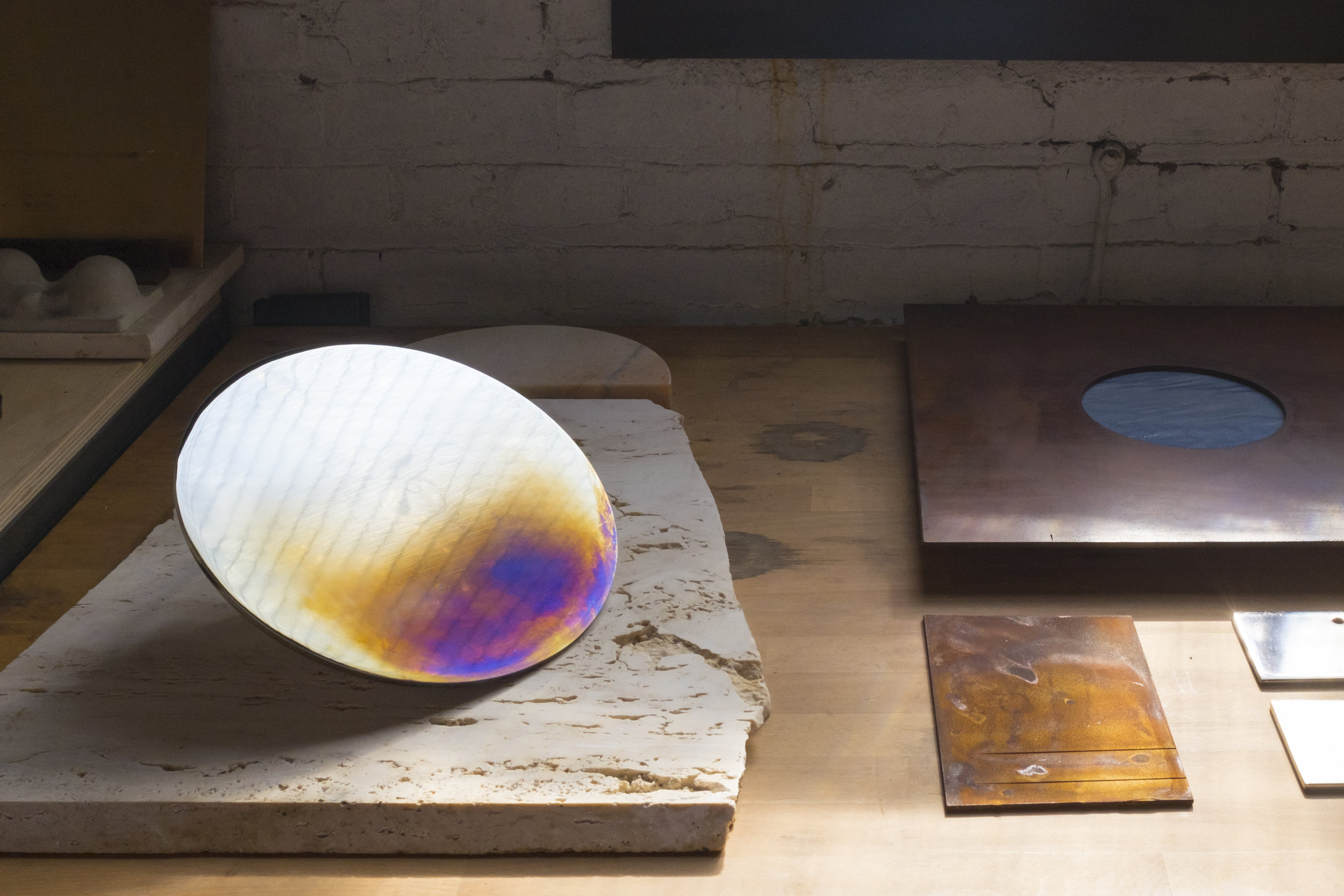

J: That’s one form of creation. The other form is where we just look at material for the sake of material; there’s no anticipation of a specific piece of furniture that we want to make.

Describe your creation process.

J: The creation process in and of itself has a whole other set of iterative phases. For example with the Thin Series, the first thing we had made was a small table. For manufacturing reasons it had to be cut into two pieces. When we got those two pieces, before welding them together, we flipped one of them over. It just so happened to work perfectly as a folded chair. So the chair wasn’t even conceptualized in the design phase; it was only from having these two pieces that led to this whole other idea. That then led to the idea of having two chairs that sit back to back, which led to the creation of the Tête-à-Tête or the conversation chair, which then led to a series of undulating park benches.

K: It’s like it fractures off more and more; each iteration creates five more ideas. We can’t even be creating these things as fast as we can be conceptualizing them.

J: And I think when we’re working we have a certain openness to these kinds of happy accidents. You have to let your ego down a little bit and say that you don’t have all the answers. Being open to that workflow is really good.

K: I think that’s what collaboration is all about, being willing to be open and leave your ego aside. If you’re so stuck in your idea then you’re not going to get that benefit of growing. When someone has a different idea than you, it’s not a personal affront to your idea or to your sense of self. Thinking about the process as growth rather than control is a really important part of pushing forward in all parts of the business, especially the creative part.

How do you choose and source your materials?

J: We started working with metal as our main material. It’s very versatile. It’s rigid, it’s elastic, it can be cast, it can be stamped, it can be welded, it can be cut, it can take on a variety of finishes. Metal has always felt like a very powerful material because of its versatility, but in some ways it’s underutilized in the design world. I mean it’s utilized in every aspect of furniture—there are always metal components—but it’s not used as much in a primary gesture.

K: Sometimes we pick a material because we’re really interested in it and sometimes it’s based on availability, which interestingly becomes its own constraint. Like with one piece we considered using a certain kind of marble that was a really vivid color, but then it turned out to be three gazillion dollars so we went with a pale one instead. That took the design in a different direction, and we ended up liking it even better.

How do concept and form relate in your furniture?

K: Again and again we find ourselves drawn to moments of vulnerability, either in the piece itself or between the people interacting with it. Vulnerability is kind of like looking for something and not knowing if you’re going to get it, like putting yourself out there. It’s exactly like the openness we described before, like taking a risk. When you do that, you make the space for discoveries and growth. It’s a life philosophy, a creation philosophy, and our furniture’s philosophy. In the furniture, we were particularly interested in these individual moments, focusing on instability or tension or things that break people down a little bit. For example the Tête-à-Tête, the two part chair, only balances when two people sit together. It will fall over if you don’t sit with someone simultaneously, so you really have to open yourself up to vulnerability and trust the other person. We showed that piece at WantedDesign in May, and it was fascinating to see how people interacted with it. Some people didn’t want to sit on it and others really wanted to sit on it. Some people really trusted the person they were with, even if that person was me, a total stranger. It’s so intimate—you’re touching arm to arm—and you really have to let your guard down once you’re there because you’re in it together. It’s like the chair visually represents connection and then two sitters get to experience vulnerability and connection together.

J: I think it’s also building some sense of mystery around the object itself. It might be in the way that you approach a piece; you may see it in one orientation but when you move around it a plane shifts or a surface turns from horizontal to vertical, which forces you to ask a question about it. A lot of the conceptual ideas have to do with the furniture being somewhat provocative to the user. Like with the Thin Chair, someone will see the way that it sits against the wall and literally not know if it’ll hold their weight or it’ll fall.

Does working in New York have an influence on your practice?

K: I think that’s a great question based on what we’ve been talking about; New York is the ultimate in everything we’ve said. You’re forced to be vulnerable a lot.

J: New York pushes you constantly. Everyone around you is working the hardest they can work, doing the best they can do. I think that if you want to stay in New York and if you want to be successful, however you define success, you have to be brave and put yourself out there, but also be aggressive at the same time. I’m not sure that it affects our furniture on the practice side. But I think New York allows us to be a bit more conceptual and creative in the sense that the immediate audience we’re appealing to is so potentially receptive and open-minded to things that are weird or hard to comprehend.

What is the most challenging part of your process? Where do you find the most ease?

J: I think the most challenging part of the process is that initial foray into the development of new ideas and concepts, only because it’s the place where you have the fewest constraints. It’s both the most challenging part and the most exciting part. In some ways the I’m also at the most ease in that state. But if I was only working in that space it would be an intense roller coaster up and down. So I like being there at certain times and then getting out. The other part where I’m the most at ease is at the very, very end of the process when everything has been figured out and we’re just making something. Sometimes there’s still feedback, but otherwise we’ve gotten past the feedback loop where the material iterates into the design and we’re in the process of pure creation of an object.

K: For me the creative part of the process is where I’m the most at ease. The stuff that’s not creative, like the uncertainty of having your own business, is where I’m uneasy.

J: For sure. That’s not even uneasy; that’s the scary part. There’s the comfortable part, the part where you’re at ease, the part that’s challenging, and then the really scary part.

K: Right. But you if you don’t open yourself up to vulnerability then you don’t grow. I’m comfortable with making myself uncomfortable, but sometimes growth is pretty unpleasant. It’s like growing pains.

Is there anyone or anything that inspires you?

J: There are a lot of artists who worked in the late sixties and through the seventies that serve as creative inspiration, like Richard Serra, Dan Graham, Robert Smithson, James Turrell, and Michael Heizer. Dan Graham for distortion and perception. James Turrell for the way he uses light and creates spaces that are enveloping and atmospheric, but at the same time can just be a square or a corner. Richard Serra for his Torqued Ellipses and their sense of imbalance or destabilization. Robert Smithson for the scale of the work and the way in which you keep finding more beauty in natural materials as you get closer or further away, like in Spiral Jetty. Michael Heizer, who did Double Negative in the city over Nevada. Also Donald Judd for the very minimal quality and precision of metalwork. A lot of those artists have been very inspirational, but on the other side I’ll get inspired by looking at truly anonymous craftsmanship, like brickwork or weavings or patterns on tire treads. There are these amazing patterns and different materials being manipulated to create something really visually compelling, but it’s solely for durability or utility. It has nothing to do with design per se; it has more to do with function. I find that equally inspiring.

How have you learned what you know?

K: I always take each experience as if there’s more available to me in that experience then what’s directly being offered. So I could be in a job where I learn from my boss, but I also learn from my client, my customer, or my colleague. If you’re really paying attention and are open to new ideas, you can learn a lot from everybody around you. I feel like I’m always like a sponge. I was a huge copycat as a little kid, and my sister used to make fun of me for it. I think I’ve used it to my advantage as an adult. You pay attention and learn what they know, and then you can improve upon it afterward. First you imitate and then you innovate.

J: I think you’re right about that—imitate then innovate. I’ve worked with artists, architects, friends, people in grad school; there’s been this long line of other teachers that have played a role in one way or another. I had a few people who were instrumental in forming my process or creative thinking, like Todd Fouser and Reuben Jorsling who are the two partners at FACE Design. After I graduated from undergrad I went to work for them. They do architectural design and fabrication exclusively in metal. It was this really eye-opening education in terms of material and detailing and working with my hands in ways I never had before. Without that education, this practice would be very different, especially in terms of the way we work with metal.

What has your practice taught you?

J: The loss of the ego for sure. At all of the other places I’ve worked, and even in school, there’s been a sense of needing to show how good I am and that I know what I’m doing. Whereas here we allow our egos to drop away so that we can truly collaborate better. That’s been great. And then in general starting a small business and all the difficulties that comes with it teaches patience and persistence.

K: I feel like it teaches lessons every day. When you start your own business you can’t just be reacting; you have to set the agenda. As an employee or as a child, you can always say, “If I were the boss I’d do it differently.” You can constantly think that other people aren’t making the right choices. But then when you get into the reversed role, you really have to get in your own way and push yourself and be willing to grow. It’s pretty uncomfortable.

J: I have a cheesy answer to the question. Truman had a plate on his office desk that said The buck stops here. I never really understood that as a kid, but for whatever reason it stuck in my mind. In becoming a business owner and having employees, there were definitely series of moments when I understood what that phrase meant. It means that no matter what problem arises, no matter what difficulty I encounter, there’s no one past me. There’s no one else that’s going to have a different solution or a better solution; I have to figure this out and it’s not going to go away.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

J: There are a lot more scars. The most recent one was pretty bad; a grinder cut my hand open and there was a vein hanging out. So there are a lot of scars from grinders, which is the most obvious change. But I think they have a general sensitivity. What I try and tell other people who work with us is that you have to learn how to trust your hands when you’re making. You have to realize that your hands are able to sense physical dimensions or separations of space that are smaller than your eyes can see. The information—the sort of sensory, haptic information that you get from your hands—is more real than what you can see. So there’s a certain trust that has to happen. Also a certain amount of muscle memory. If you think too much about where your hand is or what it’s doing, you’re going to either mess up the material or hurt yourself in some way. While my hands might be getting more scarred over the years, there’s actually more sensitivity and pure trust put into them. Kira has very nice hands—fewer scars.

K: I used to make a lot more things with my hands. Now I don’t; most of the creating is with my brain. I kind of miss doing things with my hands, especially when you describe it in such a sensory way. I think there’s an element of working with your body that feels really good to humans. We’re not just big, throbbing brains; we have these bodies to do something with.

J: Yeah. There’s a lot of satisfaction in building something or making something.

K: It feels very primal in a way.

J: And personal.

Joseph Vidich and Kira DePaola in Brooklyn, New York on September 29, 2017. Photographs by Julia Girardoni.