Emily Weiner

Who are you?

My name is Emily Weiner. I’m a painter. I live and work in Brooklyn. I think that’s it, that’s usually my intro. Sometimes people like to add extra things, like she’s a curator and she’s a writer, but I’ve been slowly editing out all those things as extra descriptors because artist is already an umbrella term.

What do you make?

I make mostly paintings. And frames for paintings, which are still part of the paintings themselves. Recently I’ve been considering making backdrops and wallpaper for paintings. But that’s what I’m thinking about - what’s inside of painting and what extends outside of it.

Why paint?

I don’t know. I just love to paint; that is probably the real answer. It’s so malleable and beautiful. For me it’s so easy. Like if your native language is English why would you try to write poetry in French? Maybe because French sounds better, but it wouldn’t sound better if I said it. Painting is my medium, it’s the way that I’ve really learned how to speak.

But painting is so loaded. Those cave paintings in Chauvet that Herzog made a film about are so incredible. They’re just pigment; they’re just dirt and medium directly on a surface. Really we’re doing the same thing, though I’m not saying that I’m as talented or connected to my work as those painters were.

I think that the “painting is dead” mentality is a very patriarchal, mono-traditional thing and I don’t subscribe to it at all. I’m teaching this art history class called Contemporary Painting Since 1960. At first it was hard because there is so much scholarship on is this small, kind of teleological, end-game painting history - it was all within this framework according to Clement Greenberg. I don’t give a shit if essays proclaimed a group of fifteen, mostly male painters from the 20th century killed painting, especially now that female artists and people of color are just now having solo shows at big museums in New York in the 21st. But there so much more literature now on alternative, queer, and feminist histories telling the a different story. Obviously some people still subscribe to the idea that painting can no longer say anything new. But I think that's a one-sided view, to say that one medium - or even one way of thinking - is more valid than another. But that’s another conversation...

Describe your workspace.

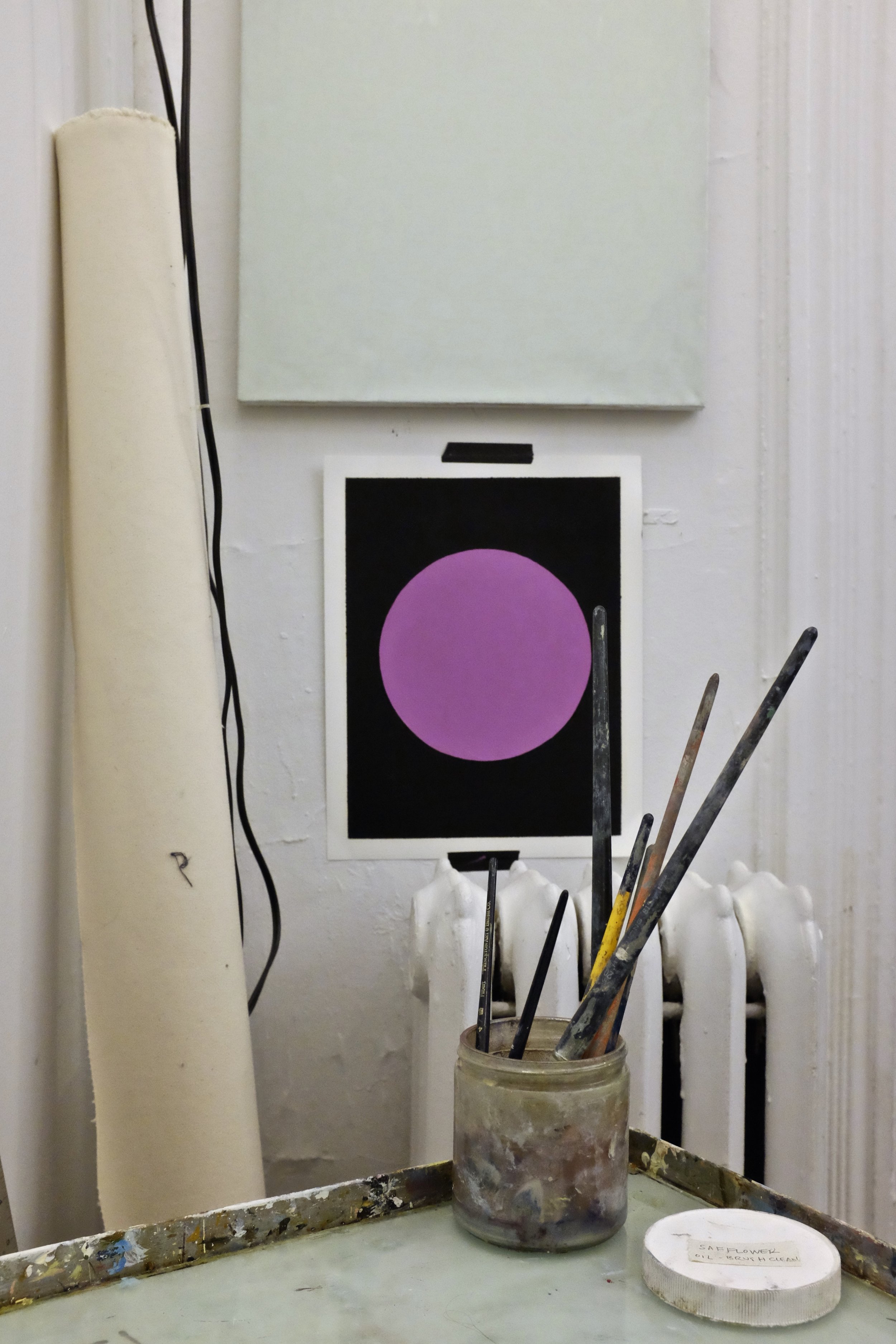

It’s a former bedroom, it’s very small. It has a window and a lot of light. I think the most important thing for me is to have white walls for a clean space. And a quiet place to work.

Under what conditions do you work best?

In the morning or early day. After 9:00 at night I’m really bad, I kind of can’t do anything. I could stretch a canvas or do something not so exciting. To get deep into a painting I need to start really early in the day, so I’ll come here in the morning after drinking my coffee and power through for four or five hours.

Do you have any rituals surrounding your practice?

I usually leave the house to get some coffee, then I come back and have to clean the studio. Even if it’s just organizing. Inevitably the studio will go from this clean state to complete chaos because when I’m working I’m moving everything, looking for tools in the closet, digging something out, mixing paint and wiping paint on the walls. There are rags all over the place and my dog Marcel drags out all the sandpaper. It’s a total mess. So cleaning and coffee. You clean the slate and then throw yourself in.

Describe your process.

It would be good to show you what a notebook looks like; usually they are full of little lists of ideas. Usually those ideas don’t come all at once. I might start a painting with one of these ideas in mind, and then incorporate another. There’s always some non sequitur reason that makes sense in my mind about why the elements exist in a painting, but it might just be totally random according to somebody else, as if I did a random Google search of images and assembled them in no particular order.

From there, the first step is usually just putting down color or a gradient or a pattern. Typically it’s a color. When beginning a painting you’re setting a stage and backdrop for something to happen on top of it. The first step is kind of a plan. It’s like you set something in motion so you have to resolve it with another action. Then usually there’s a third action that resolves that.

Does your work reflect the technical aspects of painting as a medium?

I think it does because I’m looking at so many other painters. Some of my paintings look like they’re made by different painters; the technical stuff is really different. In one painting I might use a lot of different motifs or techniques, but I don’t think about trying to point to a certain style of painting too much anymore. If I have an idea I will just pick up a brush and do it the way I think it should be expressed. Some parts of the paintings are really layered. Sometimes I’ll use really wet brush strokes to get a juicy kind of painting. And then sometimes I use a really dry brush to scumble over the top.

On one of my paintings there are little marks that have trompe l’oeil drop shadows underneath, which is kind of a nod to other painters. I was thinking about how Lichtenstein did some paintings of brushstrokes in the most technically advanced way that you could show a brushstroke in the 1960s. It’s like he wanted to take an abstract expressionist brushstroke and make it into rasterized dots. I thought, I can do that! I just made some squiggles in Photoshop and painted them. So I’m thinking about all of those ideas in the history of painting. They’re embedded in my work, but it might come through in a totally non sequitur way.

What role does the frame play in your work?

It’s kind of weird. I think it has something to do with painting being this flat, two dimensional, traditional thing and the fact that before 1960 museums always displayed paintings in frames. I wonder, Why put a frame around a painting if it’s not part of the painting? What is it, a design element? I started looking at the form of float frames of previous painters and started to make my own. And then I just started extending the oil paint onto the frames. I’d build them in wood and I’d gesso them like I would gesso a canvas. Then as I was making the painting, or when I finished the painting, I would continue it onto the frame.

Recently I have been doing ceramic frames, which came about from this collaboration I’m doing with a sculptor. I started to think about how sculpture has so much more to do with building as opposed to creating a surface or illusion; you’re actually creating something in space. I really love the different quality that handmade sculpture might be able to achieve, but I felt like just jumping into sculpture was out of my comfort zone and would just be forced. I thought I could continue my investigation of frames in a sculptural way, so I started to use ceramics to get a sense of what building with your hands might be like. Most of the frames came out more precise than I thought they would. Some look really good and straight and then one has a little more bend, which I kind of like. So that’s where the frames are now, they’re kind of additions to the paintings or extensions of the paintings.

How do your paintings engage with cultural and historical iconography?

I’ve been really interested in Aby Warburg. He’s an art historian in the way that art historians don’t tend to like. He had this really amazing practice. He had a library and he made something like an atlas where he'd put photos next to each other, like Judith beheading Holofernes next to a figure swinging a golf club. There would be this synchronicity between the various images that he was showing. There was no research there, aside from the fact that Aby Warburg was like, “Guys, look. The same thing is going on in these two images!” I really like that. Sometimes I’ll look at them and think that they have nothing to do with each other, and sometimes they’re really great. It’s like Carl Jung and The Red Book, some kind of collective unconscious and connection to imagery that cycles through cultures and generations. Maybe there is something fossilized in an image, that in our DNA we react to or connect with, like a frequency. Something as simple as a circle can be a loaded shape.

My work from previous shows was a lot more about these ideas of symbology and iconology. One of my paintings, Mona, has a triangle like the masonic pyramid, which is also like the sacred geometry of Mona Lisa. The triangle is just like a structure of power, it has this trinity. Then I did a series of paintings of moons, including one called Phoebe. NASA named most of the moons of the planets in the solar system after the names of Titan goddesses, like Phoebe. I really liked this idea that there are still traces of these ancient religions in our contemporary society’s belief systems. So in this way we’re still looking at the heavens and talking about ancient Greek mythology. Another painting, Sappho, was an Aby Warburg tribute where there’s some kind of visual pun - something clicks. The writing is from a sculpture that I saw of the poet Sappho. It was actually a Roman copy of a Greek original. So I stole that lettering, which matched up with the painted pattern behind it of textiles from the Congo. I also did this Venus painting with a gold foil frame. I collect a lot of magazines; I had a couple of Playboy’s from the late sixties. In the centrefold of one is a really plain looking woman. At first I wondered why they chose that image but it eventually became really clear that it was powerful only because she was standing like Botticelli’s Venus. Her pose was so powerful that she became the centrefold for 1969’s November issue. I ripped out the image and it was on my board for a while. I decided to paint the image because it was the most classical pose there is.

As an artist who’s very aware of the power of imagery and symbolism in society, I guess I still don’t even recognize how much I’m influenced by the history of images. How can you take charge of all of these things filtering through your consciousness? In my studio, at least, I try to conjure the ghosts of them and get them to behave in some way, or say something back to me with more meaning on a gut level rather than a topical, commercial level.

What’s the most challenging part of your process? Where do you find the most ease?

The hardest part is figuring out how to find content for a painting. There’s this nugget that you’re always searching for, a core that you’re always circling around. And you can say it in so many different ways, but only you know when it’s right. With painting I have to figure out that perfect combination of imagery, color and form so that it clicks into place and revolves around something central that I’m always trying to get closer to. Because of that, there’s a lot of failed imagery and a lot of wiping away. One painting went from looking like a really well-rendered Roman bust to a Picasso kind of figure to a harlequin pattern; it’s the topography of covering up and taking every step; going and going until something seems to click in place. It’s a real struggle, it feels like you’re actually wrestling something. But then the easiest thing is the technical part. Once I know what to do, then it’s easy. I know how to paint, sometimes I just don’t know what to paint.

How have you learned what you know? Did you have any teachers or mentors who helped shape you as an artist?

Yeah. I realize now that my worst critique was my best critique. I had Marilyn Minter as a teacher, and the first time she came into my studio she gave me a great critique. Then the second time that she came in it was like she’d never been there before and she told me that I needed to learn how to paint. I was thinking, What? What do you mean? I’m painting! Now I realize that what she was talking about was that you can’t just start painting the same way you can’t just pick up a guitar and play; you have to practice, you have to know how the medium works and get used to it. She was right, but at the time I had no idea what she was talking about. I’ve seen her lecture about this idea; she shows her earlier work from graduate school and calls it bad painting. She’s thinks whatever somebody is showing you at the moment is the best that they can do at that moment. But it’s bad until it’s good. My best teachers were also other students at school; I’d go into their studios and ask them how they did something. An artist named Miyeon Lee was my studiomate after school for a long time. She had worked as a studio assistant for an artist who showed at Metro Pictures named Gary Simmons. So she’s the one that taught me all this technical stuff like how to stretch canvases this way. It’s really about talking shop and asking people, Can you show me that? Can you come into my studio and show me? Can I look at what you’re using?

How has your practice evolved over time?

I definitely feel like I had a late start with the technical stuff, because in undergrad at Barnard nobody teaches you how to paint, so you have to figure it out on your own. Coming to Barnard and speaking about art is so inspiring, but it’s not what you hear in art schools necessarily. Those students in art schools know how to paint and they’re bored of technique by the end. It’s almost like the stuff that I was so excited about in my first ten years of painting, at art school they learned it freshman year. Neither is better or worse, I just think that the technical aspect was part of the chase for me. I had to figure it out. Now the technical stuff doesn’t seem daunting at all; that’s the easy part. Sometimes I try to deprogram myself from making a pretty painting because I don’t want it to be slick. I don’t want something to be too rendered or too pretty.

What has painting taught you?

I think that not knowing the answers is a really good thing. That’s something that always caused me a lot of anxiety - not knowing what’s going to happen next. But all of those questions are actually just constants in your life, and those are the things that keep it really interesting in the studio. The things that you’re excited about are questions like What is this going to be? What is going to happen with this painting today? So maybe in a way painting has taught me patience. Some paintings are throwaways, but mostly when you look over the course of the year you have a few good ones. I think if you really follow the thread, it’s going to come back around. It’s going to work out.

How has your practice shaped your hands?

Oh my god. I have no idea, that’s an interesting question. I think I appreciate my hands a lot more. They’re the same hands, they’re just a little older looking. Recently I was sitting next to an artist that I really admired, and seeing her hands so close felt like I was too close to a national treasure. I was thinking, Isn’t there supposed to be glass or something?

Emily Weiner in Brooklyn, New York on October 28, 2016. Photographs by Julia Girardoni.